The age of the paratrooper arrived with the Second World War. For a brief yet significant period until the rise of the transport helicopter, paratroopers were the only effective way to launch airborne invasions, bypassing defensive lines on land and hostile fleets at sea. The first great paratroop invasion, and one which proved the decisive yet costly power of aerial landings, was the German invasion of Crete in May, 1941.

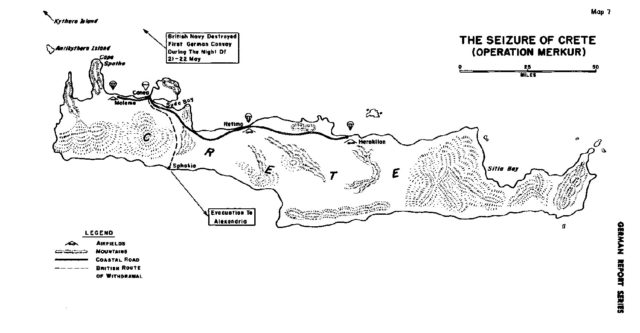

An invasion of Greece by German and Italian troops drove the British out by the 11th of May, 1941, making up for Italy’s previous failed invasion. But the British retained control of the large island of Crete and its airbases. Hitler was preparing to invade the Soviet Union, while at the same time continuing his war against the British in North Africa. Crete was important for both campaigns.

Only 200 miles from the British base at Tobruk in North Africa, Crete defended supply lines to Africa. If it could be taken, then it would be harder for the British to maintain troops in the one land theatre where they were successfully fighting the Axis.

The Cretan airbases lay within striking distance of the Rumanian oilfields, which provided vital fuel for German troops. The invasion of Russia, though intended to secure oil supplies in the long term, would temporarily deprive the Germans of Russian fuel as trade ended. The British bombers had to be kept from those oilfields.

Why Crete?

Crete’s Defenders

The Allied forces on Crete were led by General Bernard Freyberg. A distinguished veteran, he had been wounded 27 times in the First World War. But following a series of quick command changes, he took over the island just three weeks before the Germans arrived, giving him little time to prepare for a defence.

The largest group of soldiers on the island was a 17,000 strong British force. Alongside them were 10,300 native Greeks, 6,500 Australians, and 7,700 New Zealanders, who would play a vital role in the fighting to come.

Bombing by the Luftwaffe destroyed most of the RAF aircraft on the island, and the rest were withdrawn to safety in Egypt. All Freyberg had to defend the skies were 68 anti-aircraft guns – less than one for every two miles of the length of Crete.

The Landings Begin

Early on the 20th of May, 1941, the first German troops approached the island. Supported by 500 bombers and fighters, 500 transport planes and 72 gliders soared over Crete.

Some of the landings were a success. Landing around the Máleme airfield, they took Tavronitis Bridge from the New Zealanders. The 1st Company of the 3rd Parachute Regiment seized and spiked an Allied anti-aircraft battery.

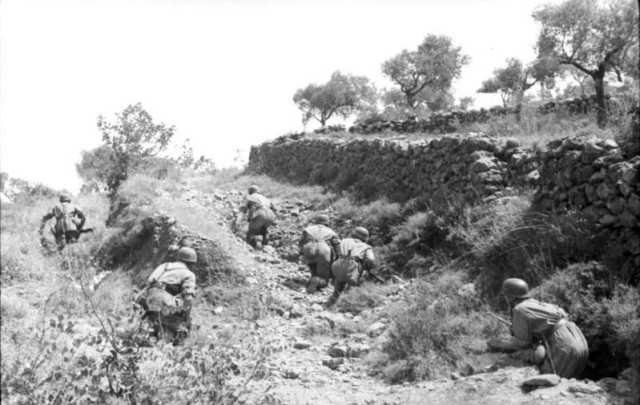

Others were less successful. Many of the paratroopers landed among enemy troops and as a result suffered heavy casualties. Entire units were wiped out.

Scattered and Struggling

Scattered across the island, the Germans found themselves easy prey for the Allies. Heavy mortars were lost after being dropped over a reservoir. Divisional commanders were lost in a glider crash. An HQ was set up, but when the second wave of paratroopers arrived they were unable to fulfil any of their objectives.

The shock of their arrival provided a setback for Freyberg. Knowing how little time he had had to prepare and that his troops had lost vital equipment in the withdrawal from mainland Greece, he was pessimistic about the battle. Despite having superior numbers, he made no attempt at a counterattack on the night of the 20th.

The next day, confusion and rumours of defeat led to the real defeat of the 22nd New Zealand Battalion, letting the Germans capture the airfield at Máleme. Now they could fly in ammunition on transport planes.

The New Zealanders Counterattack

The Allies had some successes. The first flotilla of sea-borne Germans was sunk by the Royal Navy, and a second driven back. Though the British fleet suffered heavily at the hands of the Luftwaffe, they had blunted part of the German attack.

On the night of the 21st, the New Zealanders launched a counter-attack against the captured airfield. East of the airfield, they ran into the remnants of a badly hurt German parachute battalion. Though scattered, these men put up such a fierce fight that the New Zealanders could not reach their objectives by dawn. Then German fighters and dive-bombers attacked, forcing the New Zealanders back once and for all.

Fresh Troops and Advances

On the 22nd of May, fresh German troops arrived, including their commander, Major-General Ringer. He divided the troops into three battle groups which launched a three-pronged attack at dawn on the 23rd.

Despite fierce fighting against the Cretan resistance in the north and the New Zealanders in the east, the Germans drove the Allies back, pushing the defenders’ artillery out of range of the airfield. Now the Germans had free movement on and off the island.

Strong advances on the 24th and 25th of May let the Germans link up with others of their comrades, taking strategic roads and villages. In another counterattack, the New Zealanders retook a village called Galatas but were left too depleted to hold it.

Evacuation

On the 27th of May, Freyberg gave in to the inevitable and ordered an evacuation. With the Germans controlling the surrounding seas and skies, there was no way that the British could hold Crete.

At great risk, Admiral Andrew Cunningham ordered the Royal Navy to carry out the evacuation. When challenged on the danger he was putting his ships in, Cunningham said “It takes the Navy three years to build a ship. It would take 300 years to rebuild a tradition.”

Starting on the night of the 28th, the Allies were evacuated through the small port of Sphakia. 8,800 British, 4,704 New Zealanders and 3,164 Australians made it off Crete. 11,835 remained behind as prisoners of war.

Never Again

The Germans had succeeded but at a cost unacceptable to Hitler. 3,714 men were dead, 2,494 wounded – more losses than in the entire Balkan campaign. The Fuhrer forbade further paratroop invasions. But Crete was now his, and the invasion of Russia could go on.