The early days of World War II were strangely quiet across much of Europe. The invasion of Poland was followed by what U.S. Senator William Borah labeled the “Phony War.” While China and Japan fought what was then a separate conflict, the European powers sat staring at each other. Britain and France had declared war on Germany, but where was the fighting?

The Fate of Poland

For the Poles, there was nothing phony about the fighting that started in September 1939. Their country was overrun by the German army from the west and the Soviet army from the east. Within weeks, the nation was fully occupied, the government on the run, and large parts of the army were fleeing south across the border, looking to continue the fight from abroad.

The invasion of Poland led half a dozen countries to declare war on Germany. Australia, Canada, South Africa, and New Zealand were all too far away to have an immediate impact. Only Britain and France were in a position to have an impact on the fighting.

Despite their previous reassurances, they didn’t leap to defend Poland. They had no troops in the area at the time and hadn’t yet mustered the political will or military capacity to begin sending any. The Poles pleaded with the British to bomb German air bases, but the British refused. They feared that if they bombed the Germans before the Germans bombed them, they might alienate the Americans.

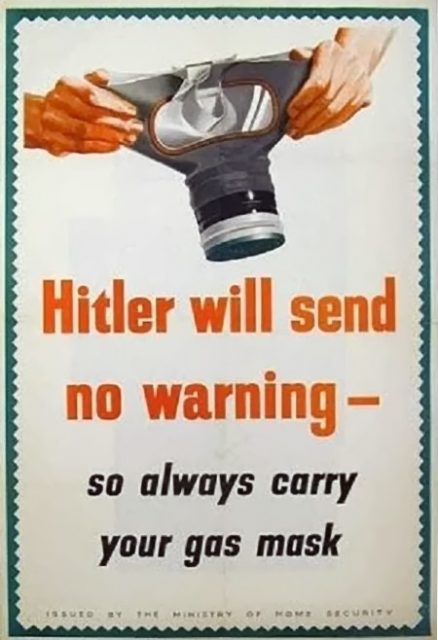

The Confetti War

Though they weren’t ready to bomb the Germans, the British government did send its planes. Over the course of September, British bombers dropped over 18 million propaganda leaflets across Germany, in what former army officer and Conservative MP Edward Spears mockingly labeled a “confetti war.”

There were two purposes to the leaflet campaign. One was to try to convince Germans that Hitler’s government was evil and should be opposed. The other was to prove that the British could reach them, thus provoking fear.

Neither aim succeeded and several bombers were lost.

The Western Front

Before the war, the French had promised that if the Germans invaded Poland, they would invade Germany to take pressure off the Poles.

This invasion never took place. The French made a limited incursion into the Saarland, then hastily withdrew when German reinforcements appeared. Along most of the border, there was no action at all.

The French, like the British, made excuses for their inaction. Their army wasn’t ready. Their air force was too weak. The German defenses were too strong. But again, the lack of political will was crucial.

Meanwhile, tens of thousands of British personnel were shipped across the Channel. The British Expeditionary Force (BEF) joined the French along the border, just as its namesake had done in 1914.

On both sides of the border, troops dug in, preparing more defenses. Once Poland fell, the Germans moved troops west, many of them now experienced combat veterans. Any chance the Allies had of delivering a quick blow against the enemy was gone.

In early December, the BEF suffered its first casualty, when British and German patrols unexpectedly clashed. But for the most part, the soldiers spent their time training and waiting.

Peace Overtures

With Poland secured, Hitler talked about peace. His overtures were roundly rejected by the British and French. Having finally been stirred into action, they were not willing to stand down until Europe was safe from further German aggression. Without significant German action to show a change of direction, there could be no talk of peace.

This suited Hitler. The real audience for his peace initiative had been his generals, who were worried by his aggressiveness and feared that, while they were busy in the east, Germany might be vulnerable in the west. Hitler had given them what they wanted – an attempt to limit the scale of the war. Now that they felt he had listened, they were more willing to follow his plans.

Belgium and the Netherlands were both rightly worried about becoming caught up in a war between more powerful states. They too tried to negotiate peace between the great powers. But Hitler had made his point, and had no need to play along with anyone else’s peace plans.

Changes in Government

Meanwhile, the leadership of both Britain and France was called into question.

In Britain, Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain’s position had been seriously weakened by his pre-war appeasement of Hitler. Though he tried to take a tougher tone now, he was struggling both with politics and with self-doubt. He moved Winston Churchill into a more prominent position, but remained in power until after the phony war reached its end.

French Prime Minister Édouard Daladier didn’t fare so well. By March 1940, he had broken France’s promises to support Poland against the Germans and Finland against the Soviets. It looked increasingly likely that the French would end up fighting on their own soil. Daladier resigned and was replaced by Paul Renaud.

The War at Sea

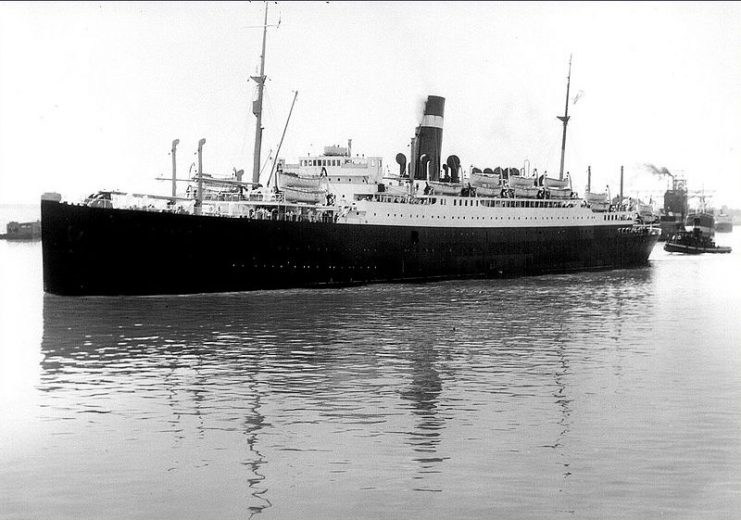

Though there was little action on land, the British and Germans immediately began fighting at sea. Within hours of the British declaration of war, a German U-boat sank the passenger liner Athenia, allegedly mistaking it for a cruiser.

Over 140,000 tons of British shipping was sunk by the end of September, though the German success rate sharply declined over the course of the month.

In October, a German U-boat penetrated the British naval base at Scapa Flow and torpedoed HMS Royal Oak.

But the most exciting naval confrontation of the Phony War took place in December, off the coast of South America. There, three British ships cornered a larger German raiding vessel, the Graf Spee. After a sharp fight and a day of pursuit, Graf Spee was trapped in neutral territory and effectively taken out of the war.

The Coming Storm

On 8 April 1940, the British Royal Navy began laying mines in the coastal waters of neutral Norway, the first real British effort to advance the fighting in Europe. The next day, Germany invaded Norway.

Read another story from us: The Soviet Invasion of Poland, 1939

The phony war was over. Now the real one would begin.