Throughout the Second World War, the people of Poland were stuck between Germany and their old enemy, the Soviet Union. In September 1939, the country fell to the Germans, and the prospect of freedom was looking very bleak come 1944. However, they couldn’t just give up; they were faced with either German rule or Soviet domination, which meant they had to keep fighting. This is what led to the Warsaw Uprising.

Things were looking bleak for Poland

The Soviet Red Army was rapidly approaching from the East, and after the Katyn Massacre, when the USSR executed thousands of Polish officers, fighting between the Polish Resistance and Soviet partisans in Poland only intensified. With Joseph Stalin‘s unquenchable thirst to draw more countries into the Soviet Bloc, many Poles were worried one conquerer would be replaced by another.

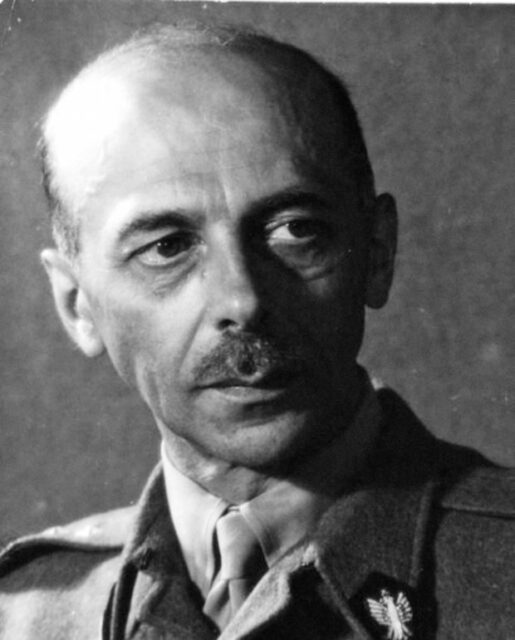

With this bleak prospect looming on the horizon, Commanding Officer Tadeusz Bór-Komorowski of the Polish Home Army, also known as the Resistance, devised Operation Tempest: a huge, coordinated effort by the underground to rise up across the nation, with a focus on Warsaw, to kick the Germans out before the Soviets swept into major cities on the west side of the Vistula.

It became the largest military operation by any Resistance movement in an occupied country during World War II.

Losing the Red Army’s support

Though wary and distrustful of the Soviets, the Polish Home Army timed their uprising with the approach of the Red Army via Eastern Poland, in the hopes they’d offer some assistance or, at least, divert the Germans from Warsaw. In actuality, it was the opposite that happened.

Firsthand accounts from people living in Warsaw at the time claim Russian aircraft that were previously heard flying missions against the Germans in the weeks prior to Operation Tempest suddenly stopped all activity when it began. Joseph Stalin had ordered his troops to halt their advance toward Germany and issued direct orders that all support for the Home Army’s efforts should be cut off.

What’s more, he said any Home Army units in Soviet-controlled areas should be apprehended and disarmed.

Beginning of the Warsaw Uprising

Nevertheless, four days after Operation Tempest began, on August 1, 1944, the Polish Home Army was in control of a large swath of area in Warsaw, meaning the fight was on for the liberation of the city. Many in the Resistance had been training in urban combat for years in preparation for such an engagement, but they weren’t ready for a prolonged struggle against the professional soldiers of the Wehrmacht and the viciousness of the SS.

The Germans’ reaction to the uprising was swift and brutal. The Reichsführer-SS ordered his men to crush the Polish Resistance, leading to the massacre of civilians in Warsaw’s Wola district. On August 5, the SS murdered tens of thousands of civilians of all ages and genders. By the end of the Warsaw Uprising, as many as 200,000 civilians were killed in and around the city.

Refusing to back down

The Germans quickly noticed that the mass killings only seemed to strengthen the resolve of the Polish Resistance and changed their focus to taking back the city – street by street, house by house.

The Polish Home Army had between 20,000 and 50,000 active members. While the Germans had begun with around 25,000 troops, this number quickly ballooned with the arrival of reinforcements and tanks, all tasked with retaking Warsaw. The battle quickly became a bloody stalemate, with the Germans using everything from continuous, widespread bombings to tanks with human shields.

The Poles had set up many barricades and ditches, however, making any progress by German armor very slow.

Talks between the Polish Resistance and the German military

Throughout the month of August, the Germans made slow, steady progress. Section by section, the Resistance fell, and, by early September, Tadeusz Bór-Komorowski agreed to talk to the enemy, which made progress over several days and achieved things like the evacuation of 20,000 civilians.

The talks were broken off by September 11, however, as the Red Army was, once again, pushing forward against the Germans. By September 13, the enemy combatants had retreated across the Vistula and destroyed bridges.

This brought a great deal of renewed hope to the Polish Home Army. Unfortunately, all help they finally did receive was either too little, too late or both. Not wanting to anger Joseph Stalin, it took Britain and the United States a woefully long time to airdrop supplies into Warsaw. Containing food, weapons, ammunition and medical supplies, these drops were too few and often landed in German-controlled areas.

A promise of reinforcements

Perhaps the biggest boost to Polish Home Army moral came when Gen. Zygmunt Berling, who led a division of the Resistance in the Soviet Union and committed troops to reinforce his countrymen. Had this move come several weeks earlier, it might have helped. However, after weeks of fighting, the Germans had regained control over all but a small sliver of the Vistula’s west bank.

Even with some artillery and air support from the Red Army, the units attempting to cross the Vistula experienced little success. Just 900 men managed to get across and help their comrades, outweighed by heavy losses, as they suffered 5,600 casualties.

End of the Warsaw Uprising

After many pleas to the Soviets for help and with no answer, the Polish Home Army ended the struggle on October 2, 1944. The Germans retook full control of Warsaw, and the city’s remaining population was taken out of the city and moved to prisoner of war (POW), concentration and labor camps, or relocated to other areas in Poland and Ukraine.

The Germans then proceeded to level much of the city. Between destruction from the overall war, the earlier uprisings and the reaction to Operation Tempest, approximately 85 percent of Warsaw was totally destroyed. The Germans primarily destroyed monuments, museums, academic institutions, libraries and archives.

More from us: Audrey Hepburn Risked Her Life to Help the Dutch Resistance During World War II

Want War History Online‘s content sent directly to your inbox? Sign up for our newsletter here!

After the Soviets “liberated” Warsaw and the rest of Poland and instituted their own rule, talk of the Warsaw Uprising was actively suppressed. Leaders of the Home Army and other Resistance groups were smeared as German collaborators, put through mock trials and sent to the gulags. It was decades before the brave freedom fighters of Warsaw were commemorated for their heroism.