His gesture remains engraved in the minds of people around the world, yet August Landmesser’s name is not widely known. He is the man in the iconic photograph which depicts a crowd performing a Nazi salute, while he defiantly stands with his hands crossed.

The picture was taken on 13th of June, 1936, when Adolf Hitler attended the launch ceremony of the naval training vessel, Horst Wessel at the Blohm + Voss shipyard in Hamburg. The men in the photograph were all workers from the shipyard.

This sort of disobedience was considered very insulting in Nazi Germany, and Hitler spent his first years in power purging the ones who opposed him.

To understand Landmesser, we need to dive into the historical context of post-WWI Germany. The Versaille Treaty sealed the fate of German economy, which was already devastated by the first world war. The unemployment rate was extremely high. Some reports state that in 1926, there were two million unemployed Germans. By 1932, the number had risen to six million.

The black market was booming, as unemployed men and women were becoming more and more dissatisfied with the Weimar government. The Nazi Party seized the momentum, by enabling jobs for their members. With a strong lobby, they attracted more and more people to join them.

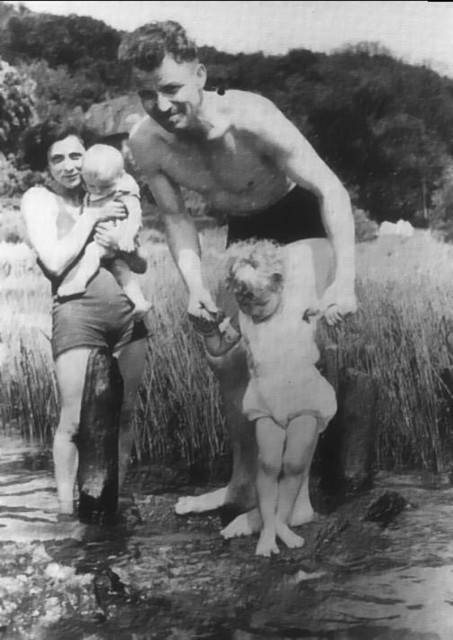

As the situation became worse, people were easily seduced by Hitler’s aggressive rhetoric, but many joined only to survive. August Landmesser became a Nazi Party member in 1931, two years before Hitler was appointed Chancellor of Germany. He wasn’t keen on the whole “racial purity” narrative, but he kept his head down, in order to get a job. In 1935, he fell in love with a Jewish woman, Irma Eckler, and they became engaged soon after.

The couple was waiting for a child. This alone was enough for him to get expelled from the Nazi Party, but he didn’t mind. His wedding plans were violently interrupted when a set of racist laws was enacted. The infamous Nuremberg Laws introduced the official racial policy of Nazi Germany.

The Law for the Protection of German Blood and German Honour was in effect, which stated that “Marriages between Jews and subjects of the state of German or related blood are forbidden. Marriages nevertheless concluded are invalid, even if concluded abroad to circumvent this law” (Article 1.1) and “extramarital relations between Jews and subjects of the state of German or related blood are forbidden” (Article 2.1).

The laws came into force on the 15th of September, 1935. On October 29th, just one month later, Landmesser’s and Eckler’s daughter, Ingrid, was born. The Nuremberg Laws explicitly forbade any sort of relationship, let alone marriages, between Jews and Germans, so the couple remained unmarried.

Raising a child with a Jewish woman, who wasn’t legally his wife (nor she could be), in Nazi Germany was hell, but what followed was far worse.

After experiencing humiliation and fear for almost two years, Landmesser decided to flee Germany in 1937. Together with his family he tried to cross the border with Denmark but was apprehended. August Landmesser was accused of “dishonoring the race.” He was found guilty in July 1937 but managed to get acquitted due to lack of evidence.

Irma Eckler, even though Jewish by origin, had officially adopted the Protestant religion after her mother remarried. The two claimed that they were unaware of Eckler’s Jewish ancestry.

They were still forbidden to leave the country but were at least free from charges. The court issued a warning, which stated that a repeat of the offense would land him in prison.

Irma Eckler was pregnant at the time, and the two refused to part, in spite of the law. This led to the promised consequences. Eckler was arrested by the Gestapo and held at the prison Fuhlsbüttel, where she gave birth to a second daughter, Irene.

From there she was sent to the Oranienburg concentration camp, the Lichtenburg concentration camp for women, and then the women’s concentration camp at Ravensbrück.

There are several letters sent by Irma Eckler that verify her locations until 1942 when she was sent to Bernburg Euthanasia Center, where she suffered the fate of 14,000 other prisoners. In 1949 her death was confirmed through official documents. As for August Landmesser, he served his sentence in a regular prison.

He was released on 19th of January, 1941. By this time, the war in Europe was raging. The Nazi war machine needed a constant flow of workers, so Landmesser managed to get a job as a foreman with the haulage company Pust.

The company had a branch at the Heinkel-Werke (factory) in Warnemünde, which was the Heinkel company headquarters. Landmesser managed to spend most of the war as a worker but was drafted into the Strafbattalion units in 1944. These were the penal battalions composed of convicts, criminals, political opponents, and the like.

They were usually sent as cannon fodder, and the life expectancy in the penal units was extremely low. Officers and enlisted men in the Strafbattalions were stripped of all insignia and wore a red triangle that represented their position in the Army.

Landmesser was pressed into service as part of the Infantry. His battalion was stationed in the Balkans, mostly responsible for anti-partisan actions and guard duty. He was first declared missing in action after being killed on 17th of October, 1944. Like Irma Eckler, his death was confirmed in 1949. Their children, Ingrid and Irene, survived the war.

The marriage of August Landmesser and Irma Eckler was recognized retroactively by the Senate of Hamburg in the summer of 1951, and in the autumn of that year, Ingrid assumed the surname Landmesser. Irene continued to use the surname Eckler.

In 1996, Irene Eckler wrote a book titled The Guardianship Documents 1935–1958: Persecution of a Family for “Dishonoring the Race.” Her father remains a symbol of rebellion to this day. The photograph taken in 1936 sums up the disobedience of German individuals who all suffered a terrible fate under the Nazi regime.