The Nazi government under Adolf Hitler saw architecture as a means of imposing fear and respect. Hitler, like many Germans, had an admiration of the ancient world, especially Greece and Rome.

In a time when art was changing rapidly, he deemed the avant-garde movement as degenerate.

Together with his chief architect, Albert Speer, Hitler revived a conservative, monolithic architectural style that impressed and scared many at the same time.

The Thousand-Year-Reich was to be demonstrated through the aesthetics of these structures, which showed Hitler’s undeniable power within Germany.

Even though many of these buildings never survived the war, some were spared the destruction, to remain as painful reminders of the regime, or to be put to use once again.

In this list, we will concentrate on some of those structures that are still present today.

10. Olympiastadion Berlin

The home of the most infamous Olympics ever to take place in history was built on the foundation of the Deutsche Stadion in the Grunewald Forrest.

The Summer Olympics in Berlin were scheduled in 1916, long before Hitler came to power, but they were postponed until 1936 due to World War I and the economic crisis.

Hitler saw the opportunity to stage a great propaganda event that would prove German superiority and align the German people as the successors to the Greek tradition.

The architects of the stadium were Albert and Werner March, the sons of Otto March who was supposed to handle the project before Hitler’s chancellorship.

Construction took place from 1934 to 1936. When the Olympiastadion was finished, it was 1.32 square kilometers (326 acres).

It consisted of (east to west): the Olympiastadion, the Maifeld (Mayfield, capacity of 50,000) and the Waldbühne amphitheater (capacity of 25,000), in addition to various places, buildings and facilities for different sports (such as football, swimming, equestrian events, and field hockey) in the northern part.

Even though German athletes collected most of the medals in the 1936 Summer Olympics, the success of Jesse Owens, an African-American sprinter who garnered four gold medals in the sprint and long-jump category, infuriated Hitler.

The stadium and the Games that took place in 1936 were depicted in a 1938 documentary film by Leni Riefenstahl, titled Olympia.

Today, the building is the home of the Hertha BSC football club.

9. Olympic Village Berlin

In addition to the giant stadium, an Olympic village was built in 1934. It is located at Estal in Wustermark, on the western edge of Berlin.

The site, which was 30 kilometers (19 mi) from the center of the city, consisted of one and two-floor dormitories, dining areas, a swimming pool, and training facilities.

It housed around 4,000 athletes from all over the world during the Summer Olympics. During the Second World War, it was used as a hospital for injured Wehrmacht soldiers.

In 1945, it was taken over by the Soviet Union and became a military camp of the Union occupation forces. Some sources claim that the village has been used as a KGB torture facility.

Recent efforts have been made to restore parts of the former village, but to no avail. Efforts are being made to restore the site into a living museum.

The dormitory building used by Jesse Owens has been fully restored, and tours are given daily to small groups and students.

8. Prora Holiday Resort

Prora is a beach resort located on the island of Rugen, Germany. It was built as part of the Strenght through Joy project in the period between 1936 and 1939.

The Strenght through Joy was a large-scale, state-operated leisure organization in Nazi Germany that promoted the advantages of National-Socialism. In the 1930s, it became the largest tourism operator in the world.

Prora beach resort was designed by Clemens Klotz, who won a design competition organized by Hitler and Speer. More than 9,000 workers were involved in the project.

The central building was 4,5 km long and it was located 150 meters away from the coastline.

It included eight housing blocks, swimming pools, and a cinema theater and it was supposed to house 20,000 guests at once.

The construction was interrupted because of the war. During the war, it was used as a refugee asylum and an auxiliary female personnel resort. After the war, it ended up on the Soviet side of the Iron Curtain.

First, it became an Army Base for the Soviets and later, as the East German Army was founded in 1956, the beach resort was used for housing some its units.

It still stands today, on the island of Rugen, relatively preserved, but without further use.

7. Flak Towers

Flak Towers were structures made of concrete that were used for anti-aircraft defense and as civilian shelters during bombing raids in Germany and Austria.

In Berlin, three were built, two have survived the war and are still standing today.

Another three were built in Vienna. The L-Tower and the tower near the Obere Augartenstrasse survived to this day.

In Hamburg, two of the flak towers remained partially.

The towers proved to be almost indestructible, so there was never a large-scale initiative for their demolishment.

Several were destroyed after the war, but the ones that remained were turned into restaurants, nightclubs, or music shops.

Some of them were simply abandoned, but they remain as testaments of much darker times.

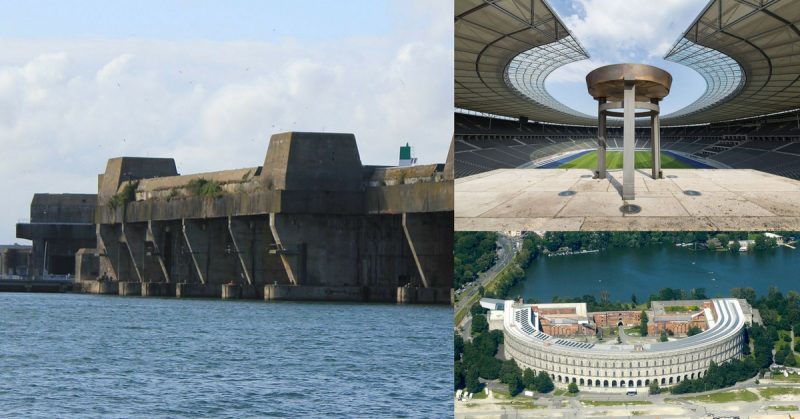

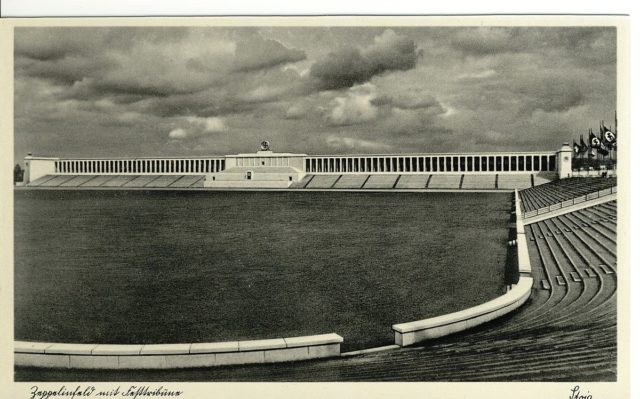

6. Nazi Party Rally Grounds Nuremberg

Reichsparteitagsgelände or the Nazi Party Rally Grounds covered an area of 11 square miles, just outside of Nuremberg.

It was the home of Nazi Party public meetings, where Hitler made his most inflammatory speeches.

The entire complex consisted of many structures, some of which built before the Nazis, like the Luitpold Hall and the Hall of Honor (which was initially built to honor the soldiers from Nuremberg who died during WWI).

The largest and best-preserved building that remains today is the Congress Hall. The foundation stone was laid in 1935, but it was never finished. It was planned by the Nuremberg architects Ludwig and Franz Ruff.

It was intended to serve as a congress center for the NSDAP with a self-supporting roof and should have provided 50,000 seats. It was located on the shore of and in the pond Dutzendteich and marked the entrance of the rally grounds.

The building reached a height of 39 m (128 ft) (a height of 70 m was planned) and a diameter of 250 m (820 ft).

The building is mostly built out of clinker with a facade of granite panels.

The design (especially the outer facade, among other features) is inspired by the Colosseum in Rome.

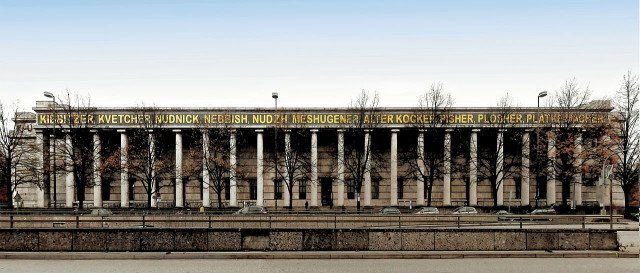

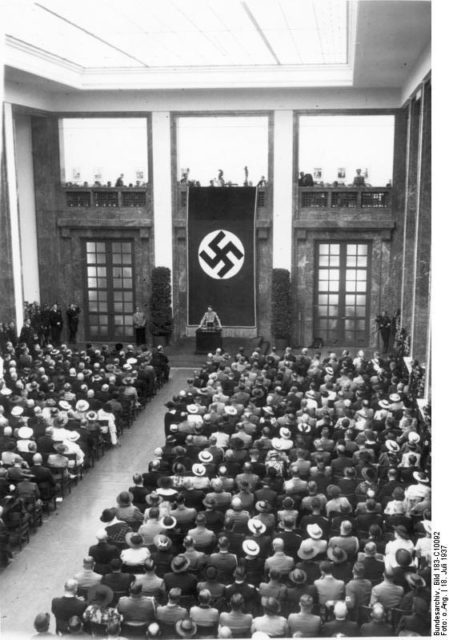

5. Haus der Kunst Munich

The House of Art in Munich ― Hitler’s own shrine to his aesthetic ideals that condemned the so-called “Degenerate art” through an inaugural exhibition titled “The Great German Art Exhibition” that occurred on 18 July 1937.

The building was designed by Paul Ludwig Troost and it is considered to be the first monumental example of Nazi architecture.

Troost was Hitler’s favorite architect (besides from Speer, of course) whose neoclassical designs were completely compatible with the dictator’s vision of the future of architecture.

Haus der Kunst was built in a period between 1933 and 1937.

In 1939, it hosted the celebration of 2,000 years of German culture ― a celebration that involved thousands of actors and an incredibly expensive scenery.

After the war, it was turned into an American officer mess hall. Later, the building was returned to its initial purpose, as it houses several regular exhibitions.

The basement of the museum was turned into a nightclub that is considered to be Munich’s most famous high-society destination.

4. Ministry of Aviation Berlin

Detlev-Rohwedder Haus was the largest office space in the world when it was constructed in 1936. The building is most famous for housing the Ministry of Aviation of The Third Reich.

It was designed by Ernst Sagebiel, a prominent architect that was also responsible for the reconstruction design of the Tempelhof airport.

The Detlev Rohwedder Haus was described as “in the typical style of National Socialist intimidation architecture,” due to its gigantic size.

It comprised a reinforced concrete skeleton with an exterior facing of limestone and travertine (a form of marble).

With its seven storeys and total floor area of 112,000 sqm, 2,800 rooms, 7 km (4 mi) of corridors, over 4,000 windows, 17 stairways, and with the stone coming from no fewer than 50 quarries, the vast building served the growing bureaucracy of the Luftwaffe, plus Germany’s civil aviation authority which was also located there.

Yet it took only 18 months to build, the army of laborers working double shifts and Sundays. The first 1,000 rooms were handed over in October 1935 after just eight months’ construction.

When finally completed, 4,000 bureaucrats and their secretaries were employed within its walls.

Today it houses the Federal German Ministry of Finance.

3. Keroman Submarine base Lorient

In 1940, Grand Admiral Karl Donitz needed a base of operations on the French shores of the Atlantic Ocean.

The notorious Keroman Submarine Base became the starting point of numerous U-Boat operations, especially the ones targeting Allied supply convoys during the U-Boat Happy Days.

In the period between February 1941 and January 1942, three gigantic reinforced concrete buildings were erected on the Keroman peninsula, near the French town of Lorient. The base was capable of sheltering thirty submarines under cover.

Although Lorient was heavily damaged by Allied bombing raids, this naval base survived through to the end of the war.

Lorient was held until May 1945 by the Nazi German army though surrounded by the American Army; the Germans refused to surrender.

The structures were so difficult to damage, that the Allies decided to flatten the town of Lorient instead, thus cutting the base from its main supply line.

After the liberation of France, the base was used by the French Navy and it was renamed Base Ingénieur Général Stosskopf in July 1946.

It was dedicated to Jacques Stosskopf, an Alsatian German who was one of the main engineers on the project, working as a mole for the French resistance.

Stosskopf was the main source of intelligence data about the base and its operations, throughout the war.

The base was abandoned by the French Navy in 1997 and it serves as a tourist location to this day.

2. NS Ordensburg

Soon as the Nazis took power in Germany, their megalomaniac leader wanted to make sure that the education system provides a constant flow of loyal party members.

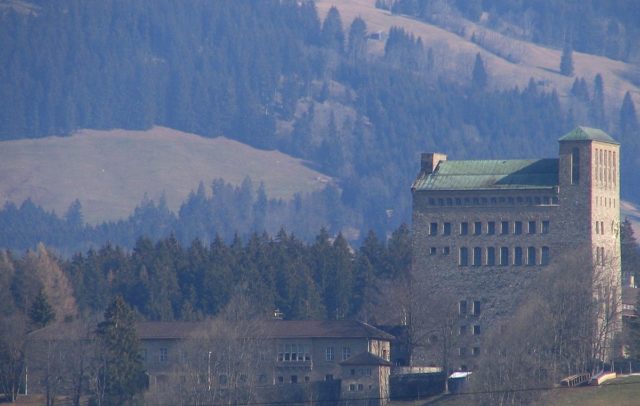

NS Ordensburg is a common name for three remote castle-like schools that were supposed to educate the future party leaders.

The first one was built in 1934, Ordensburg Sonthofen in Allgau, following the design of Hermann Giesler.

The school nurtured the elite status, as it enrolled only trustworthy candidates who were of “pure blood,” between 25 and 30 years of age, mentally and physically fit and already members of some sort of Nazi organization, whether it was the SS, Hitler Youth or the Nazi Party itself.

Besides Sonthofen, the other two Ordensburg schools were Vogelsang in Eifel and Krossinsee in Pomerania.

All schools were equipped with the state-of-art technology, sports gymnasiums, cinemas and other commodities.

With the fall of the Third Reich, the schools were used for other purposes.

All three locations were used for military purposes after the war in the countries that inherited them ― Sonthofen for the German Bundeswehr, Vogelsang for the Belgian Armed Forces and Krossinsee was left for the Polish.

Today, only Krossinsee is still in military use, serving as the headquarters of the Polish Army’s 2nd Battalion and 12th Tank Brigade.

The other two castles are turned into tourist attractions and are marked as historic sites.

1. Eagle’s Nest Berchtesgaden

Kehlsteinhaus, or as the Allies called it “The Eagle’s Nest,” was built atop of the Kehlsteinhaus summit that rises above Obersalzberg in the Bavarian Alps.

It was Hitler’s luxurious refuge, which was presented to him on his 50th birthday. Talk about a surprise party. The complex was commissioned by Martin Bormann 1937, and the entire endeavor was paid by the Nazi Party.

The large house on the top of the mountain also includes an underground tunnel with an elevator that leads to a large parking lot, 124 meters bellow.

Its construction cost about 150 million euros in today’s standards and 12 workers lost their lives building it.

The interior was decorated by the famous Hungarian-born architect and designer, Paul Laszlo. Benito Mussolini donated a large fireplace made of red marble as a token of appreciation.

On May 4, 1945, the members of the 101st Airborne Division, together with elements of the French 2nd Armored Division, conquered Hitler’s famous mountain resort.

Today the building is owned by a charitable trust and serves as a restaurant offering indoor dining and an outdoor beer garden.

It is a popular tourist attraction to those who are attracted by the historical significance of the “Eagle’s Nest.”