The Battle of the Atlantic was the longest engagement of the Second World War, with the Kriegsmarine reigning supreme in the ocean for much of the early stages. In December 1941, Konteradmiral Karl Dönitz, commander of the U-boat fleet, launched an operation that caused devastation to Allied vessels in the first half of the following year, with almost 400 ships lost in one area in particular: Torpedo Junction.

Operation Paukenschlag

The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, thrust the United States into World War II. With the nation no longer neutral, the Germans were ready to strike, with Karl Dönitz quickly putting together and implementing a plan-of-action to attack America’s poorly-guarded Atlantic coast.

Codenamed Operation Paukenschlag, the plan was the leverage the Kriegsmarine‘s experience in the Atlantic to take out vessels navigating the busy shipping lanes off the coast of North Carolina’s Outer Banks – particularly, Capes Lookout and Hatteras.

Ill-prepared for attacks along the East Coast

Even without previous experience, the U-boat crews navigating the East Coast of the United States would have been able to inflict devastation upon the vessels transiting through what became known as Torpedo Junction (or Torpedo Alley). For starters, vessels using the shipping lanes had grown complacent in the interwar years, ditching the defensive zig-zag travel patterns that had been developed to lessen the threat of enemy torpedoes.

While one might think that wouldn’t have been a big deal, given the US Navy’s presence, think again. Just a single ship patrolled the entire region, the USCGC Dione (WPC-107); other ships had been stationed elsewhere, not that they were equipped for anti-submarine patrols, should they have been moved to the area.

Then there were issues on-shore. No blackouts were implemented, meaning any vessel sailing off the coast had a bright backdrop that made it easy to spot. There were also no patrol aircraft in the region, as they’d been assigned elsewhere, and help offered by the British Royal Navy was rejected, despite the American ally having personally experienced the wrath of the Kriegsmarine‘s U-boat fleet.

Notable incidents in Torpedo Junction

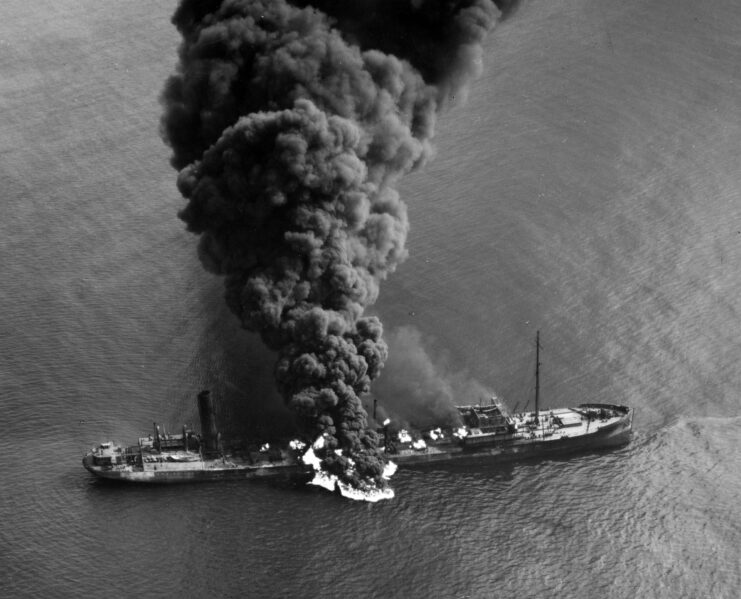

From January to June 1942, the Kriegsmarine sunk 397 Allied vessels in Torpedo Junction – a staggering number for such a short period of time, especially against a major superpower like the United States. In comparison, the American forces were only able to sink three U-boats during this timeframe.

Of the 400 overall incidents that occurred, two stand out. The first was the losses of the SS Empire Gem and Venore in the early hours of January 24. The two Allied merchant vessels were unescorted, providing the Type IXC U-boat U-66 the opportunity to attack. The enemy vessel fired several torpedoes, taking out both ships. Of their combined crews, 72 perished, while another 23 were rescued.

The second notable event involved the sinking of a German vessel. On April 13, 1942, the Type VIIB U-boat U-85 took on the US Navy destroyer USS Roper (DD-147). A firefight ensued between the two, with the latter securing a hit, before dropping 11 depth charges into the water. The enemy submarine sank, killing everyone onboard.

Criticizing the US Navy

As the number of losses began to add up in Torpedo Junction, so, too, did criticism of the US Navy. This was lost on Adm. Ernest King, commander-in-chief of the US Fleet, who failed to understand why defending the Eastern Seaboard was so important. Any patrol aircraft that came available continued to be sent elsewhere, as did destroyers, and repeated offers from the British to help continued to be turned down.

On top of this, efforts were made to keep what was happening in the Atlantic out of the media, to ensure the public didn’t panic.

One of the few military officials to recognize the importance of diverting resources to Torpedo Junction was Brig. Gen. George C. Marshall, who, at the time, was the US Army’s chief of staff. He’s quoted as saying:

“The losses by submarines off our Atlantic seaboard and in the Caribbean now threaten our entire war effort… I am fearful that another month or two of this will so cripple our means of transport that we will be unable to bring sufficient men and planes to bear against the enemy in critical theaters to exercise a determining influence on the war.”

Fighting back against the Germans in Torpedo Junction

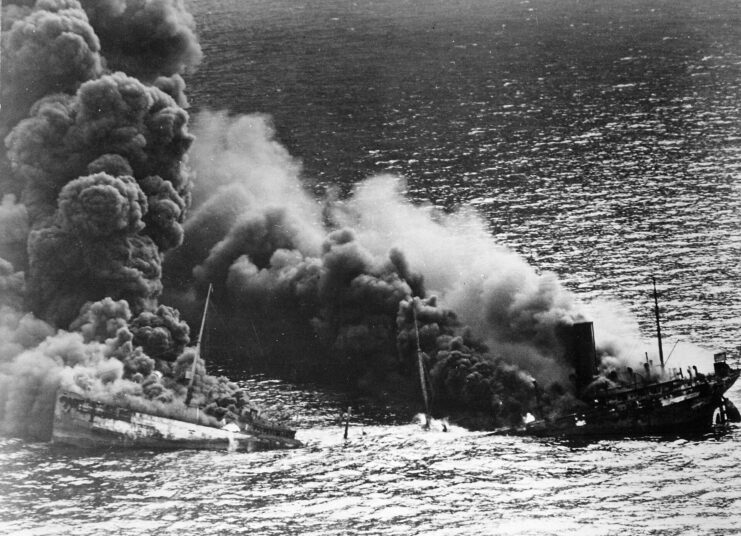

As the middle of 1942 neared, attacks in Torpedo Junction were so frequent that the flaming vessels “burned so brightly […] that on shore, it was said, one could read a newspaper by the glow at night, while the grim flotsam of war – oil, wreckage, and corpses – was strewn across local beaches.”

The insurmountable losses eventually prompted naval leadership in the United States to take action. Along with a convoy system being implemented in the shipping lanes off the Outer Banks, long-range aircraft patrols were organized and plans were made to deploy anti-submarine vessels in the region. Britain’s offers of assistance were also (finally) accepted.

Noting the increased resistance, Karl Dönitz withdrew the majority of his U-boats from the region and deployed them elsewhere.

More from us: There Are Three U-boats Entombed Beneath a Parking Lot in Germany’s Second-Largest City

Along with the aforementioned loss of ships, 5,100 people lost their lives: 5,000 on the Allied side and 100 Germans. On top of the three U-boats that were sunk, another 40 were captured.