The nuances of military history are often lost to the passage of time and with the men who could provide firsthand accounts. As much as training and battle play a significant role in the stories of war, so, too, does the camaraderie built through the nights of recreation (and, rumor has it, a beverage or two… Or three).

While there were no breathalyzers on the day to confirm the fact, by these two particular men’s admissions, they’d spent the night of December 6, 1941, drinking heavily and had gotten little-to-no sleep when the Japanese launched the most brutal surprise attack in American history. However, that didn’t stop them from loading into two Curtiss P-40B Tomahawks without orders and taking on the brunt of the massive assault.

This is a story the world knows, whether society realizes it or not. It was loosely depicted in the 2001 movie, Pearl Harbor, with Ben Affleck and Josh Harnett portraying the pair (under different names). While it was certainly full of the typically Hollywood artistic liberties, Tora! Tora! Tora! (1970) provides a much more accurate portrayal.

That being said, two audacious men took to the skies against the mightiest air assault the United States had ever experienced.

Night before the ‘Day of Infamy’

The attack on December 7, 1941, took place on a Sunday, which means that, for many on Ford Island (particularly those stationed there), a typical Saturday night was all that separated them from the day that would come to live in infamy.

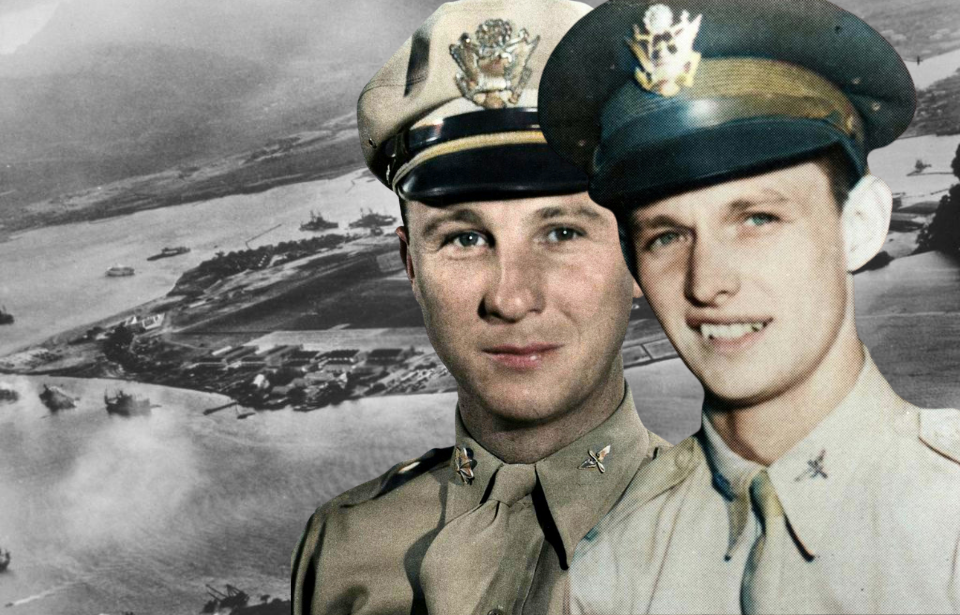

Returning to the barracks, 2nd Lt. George Welch and Ken Taylor of the 15th Pursuit Group had just returned from an epic night of partying and poker. To be musing about the night’s activities one minute and watching the attack the next must have been quite a sobering sight.

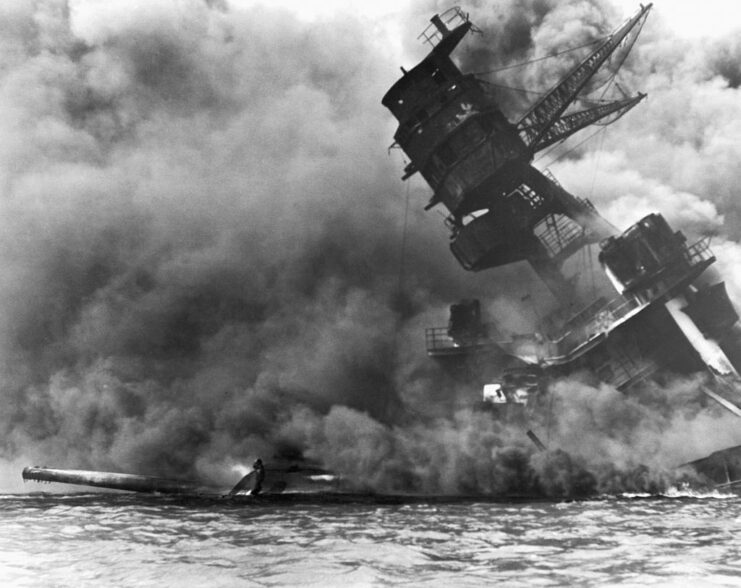

The Japanese attacked in two waves, with over 350 fighters, bombers and torpedo aircraft from six different aircraft carriers. The target was the US Pacific Fleet, most of which was anchored at Pearl Harbor at the time. When it was over, eight battleships were sunk or heavily damaged, along with three light cruisers, a minelayer, an anti-aircraft training ship and three destroyers.

Some 188 American aircraft were also destroyed, mostly sitting wing to wing on the ground, but that doesn’t mean a few brave fighters didn’t take to the sky to give the Japanese a little taste of what was to come.

Responding to the attack on Pearl Harbor

As Wheeler Field became a primary target for the Japanese, George Welch called out to Haleiwa Field to have two P-40s fueled and ready because two pilots were coming in hot… Potentially a little drunk and hungover, but coming in hot all the same.

The pair sped to the airfield in their Buick and quickly mounted the aircraft without orders, to simply do what they could. The P-40s were initially only armed with .30-cal. ammunition for the wing guns, but to these two men, that was enough to get started.

After they took off, they headed toward Barbers Point, at the southwest tip of Oahu, and initially saw an unarmed group of Boeing B-17 Flying Fortresses flying from the mainland. They arrived at Ewa Mooring Mast Field to find it being strafed by 12 Aichi D3A “Val” dive bombers (some say Nakajima B5N2 “Kate” dive bombers) from the second Japanese wave, after they’d expended their bomb ordnance at Pearl Harbor.

While Welch and Ken Taylor were outnumbered six-to-one, they immediately began firing on the dive bombers. Taylor shot down two enemy dive bombers and was able to damage another. They continued to circle the skies, fighting whatever targets presented themselves until they needed to return to base for more ammunition and fuel.

Returning to Wheeler under the threat of friendly anti-aircraft fire, they sought to refuel and load up with the more potent .50-cal. ammunition for their nose-mount synchronized machine guns. When they returned, however, the ammunition was in a burning hanger. Despite this, two brave mechanics ran into the inferno to save what they could.

Returning to the skies over Hawaii

With extra firepower, George Welch and Ken Taylor took off to face the second wave of Japanese fighters and bombers. The latter headed for a group of aircraft and, due to a combination of clouds and smoke, unintentionally entered the middle of the formation of seven or eight Mitsubishi A6M Zeros.

A Japanese rear-gunner fired at Taylor’s P-40, with one bullets coming within an inch of his head and exploding in the cockpit. One piece went through his left arm and shrapnel entered his leg. Welch shot down the aircraft that had injured his friend and Taylor damaged another, before pulling away to assist Welch in pursuing a different Zero.

The Zero and the rest of its formation soon broke off and left to return to their carriers. Taylor continued to fire on several of them until he ran out of ammunition, at which point both pilots headed back to Haleiwa. Each man insisted on returning to the sky for additional runs, without orders from their superiors – in fact, some accounts state they the denied requests from a senior officer to remain on the ground.

For their bravery, each was nominated for the Medal of Honor, but they were, instead, awarded the Distinguished Service Cross.

Fighting in World War II

After Pearl Harbor, George Welch was initially tasked with giving war bond speeches to support the war effort, while Ken Taylor was assigned to the 44th Fighter Squadron, with whom he’d go on to score additional air-to-air kills. He’d later be wounded in an air raid at Guadalcanal and was sent home to train American pilots.

Following the Second World War, Taylor remained in the service and became an officer in the newly formed US Air Force. He retired at the rank of colonel, before joining the Alaska Air National Guard, from which he retired a brigadier general in 1971.

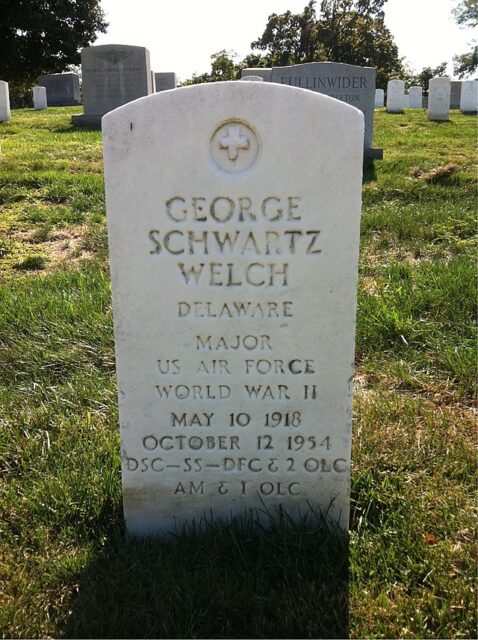

Welch’s story was a little more tragic. In 1944, he resigned his commission to become a test pilot for some of the country’s newly evolving jet aircraft. While instructing and training American pilots on these new aircraft in the Korean War, it was reported that Welch scored several MiG kills – in direct disobedience to orders – while “supervising” his students.

In 1954, while test piloting a North American F-100 Super Sabre, the aircraft broke up mid-air, ultimately resulting in his death. Welch would go on to be buried at Arlington National Cemetery.

More from us: The US Military Once Built a Japanese Warship in the Middle of the California Desert

Want War History Online‘s content sent directly to your inbox? Sign up for our newsletter here!

While the fate of these two men would take separate courses, what they accomplished in the sky over Pearl Harbor inspired a nation. They proved from early on that America was ready for a fight and that the iconic words of Japanese Adm. Isoroku Yamamoto to be true. When he said, “I fear all we have done is to awaken a sleeping giant and fill him with a terrible resolve,” it would be because men like Welch and Taylor were determined to make it so.