In the midst of World War II, the demise of German U-boat U-559 became a pivotal event in the relentless battle for supremacy beneath the waves. Nestled in the depths of the Mediterranean Sea and armed with deadly torpedoes, the vessel embarked on a mission to disrupt Allied naval operations. However, her sinister voyage was abruptly halted when she fell victim to a relentless pursuit and a daring espionage act that would forever alter the course of the conflict.

U-559

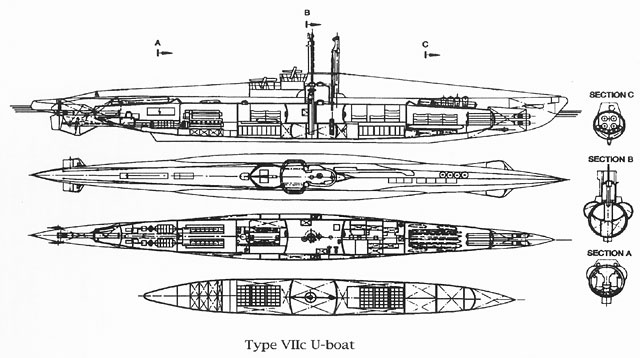

U-559 was a Type VIIC U-boat built by Germany for use during the Second World War. She was launched on January 8, 1941 and commissioned nearly two months later. U-559 was commanded by Kapitänleutnant Hans Heidtmann, who’d intended to use the vessel against Allied ships traveling in and around the Western Approaches, as part of the Battle of the Atlantic.

This isn’t what ended up happening. Instead, U-559 was briefly stationed in France, before being moved to the SMS Goeben wolfpack, the first U-boats to enter the fight in the Mediterranean. Between August 19, 1941 and October 12, 1942, she sunk five vessels and caused enough damage to make an additional two ships total losses.

However, it wasn’t these victories for which U-559 was made famous, but, rather, her own sinking.

A fateful attack

On October 30, 1942, while transiting the Nile Delta, U-559 was spotted by a Royal Air Force (RAF) crew flying overhead. The Allies immediately moved into action, with the destroyer HMS Hero (H99) ordered to intercept the U-boat’s location.

In the meantime, a member of No. 47 Squadron RAF spotted her periscope above the water and went in for the attack with depth charges. Over the following 16 hours, Hero, along with the HMS Petard (G56), Pakenham (G06), Dulverton (L63) and Hurworth (L28) continued the 16-hour hunt.

U-559 wound up too damaged to stay below the water and was forced to surface, doing so in the perfect location for Petard to open fire with her 20 mm cannon. In response, the German crew abandoned ship. Their mistake, however, was they didn’t follow proper protocol for scuttling their vessel – instead of opening the water vents into the U-boat, they simply went overboard. This meant that, inside U-559, their top-secret code books were ripe for the taking.

A war-changing discovery about U-559

At this point in the war, the Allies were mostly able to read Enigma messages. Alan Turing and his team at Bletchley Park had figured it out, thanks to coded material seized from the enemy early in the conflict. The only problem was that, in the case of the Kriegsmarine, orders were issued for a fourth rotor to be added to the previous three-rotor machine, making it, once again, impossible for the Allies to read their messages.

This changed after the sinking of U-559, when three Royal Navy sailors took drastic actions to take the coded material that lay within. The captain of the HMS Petard, the closest to the U-boat’s position, was Lt. Cmdr. Mark Thornton. He was a rather eccentric man who often made unreasonable demands of his men, and October 30, 1942 was no different, as he ordered them to board the sinking vessel.

A daring rescue

It’s unclear why 1st Lt. Tony Fasson, AB. Colin Grazier and NAAFI canteen assistant Tommy Brown were the ones to respond to the command, but they found themselves in the water. Some accounts say they stripped naked before swimming over, while Mark Thornton said they simply jumped overboard. They were able to access U-559, climbing inside to get the code books.

Brown later recalled, “The water was not very high, but rising gradually. 1st lieutenant was down there with a machine gun which he was using to smash open cabinets in the commanding officer’s cabin. He then tried some keys that were hanging behind the door and opened a drawer, taking out some confidential books which he gave me. I placed them at the bottom of the hatch. After finding more books in cabinets and drawers I took another lot up.”

A tragic end for the Royal Navy sailors

Once they’d been able to get the code books back to their comrades in lifeboats, Tommy Brown started hearing shouting on the deck of the HMS Petard. He conveyed the message to Tony Fasson as the water continued to get deeper, but he simply gave him more and more books to take up.

After depositing them, he called out to Fasson and Colin Grazier that they better come back up, but, before they could do so, U-559 started to rapidly sink. It was with great difficulty that Brown was able to reach the surface, as he was dragged with the U-boat as she went down.

He was sure there was “no chance” to save the other two, who gave their lives to rescue the German code books. Both Fasson and Grazier were posthumously awarded the George Cross, while Brown was presented with the George Medal and promoted to the rank of senior canteen assistant.

Use in breaking German code

With all the publicity, it was revealed that Tommy Brown was only 16 years old and had lied about his age to enlist. He was sent home, but never officially discharged, and was able to return to service aboard the HMS Belfast when he was of age. Tragically, Brown died only three years after the U-559 incident while trying to rescue his sister from their burning family home. He never received his medal, leaving his mother and brother to accept it after his death.

More from us: Gerhard Barkhorn Was the Second-Highest-Scoring Fighter Pilot In All of History

Little did the three sailors know that the codebooks they rescued helped solve the problem of the fourth rotor being added to the Enigma machines. They also proved to be useful when the Germans made more changes to their code in 1943.