War History online proudly presents this Guest Piece from Jeremy P. Ämick, who is a military historian and writes on behalf of the Silver Star Families of America.

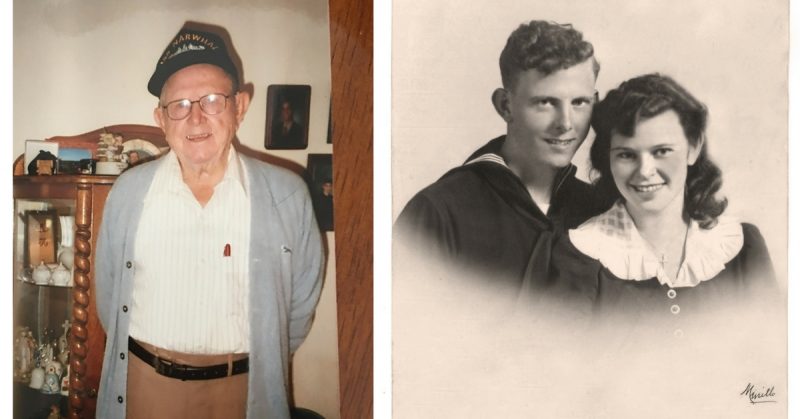

In the annals of military history, submarine service has gained a certain level of mystique, inspiring the vision of a sleek, fast underwater craft that moves about in relative secrecy in the world’s oceans. Though such visions might possess a level of truth, local submarine veteran Norbert Struemph recalls his own underwater service being far from romantic, fraught with peril and necessitating a lengthy separation from family.

While growing up in the rural community of Vienna, Mo., Struemph was raised one of 12 children. After completing the eleventh grade, he made the decision to go to work and left for St. Louis, becoming a riveter for the Curtiss-Wright Corporation.

“That’s where I was when Pearl Harbor happened,” recalled Struemph. “I remember walking downtown and people were standing in line for four or five blocks waiting to sign up (for the military).”

On June 5, 1942, six months after the attack on Pearl Harbor, Struemph joined scores of other patriotic Americans and enlisted in the United States Navy. Days later, he was transferred to the Naval Air Station once located on the site of Lambert-St. Louis International Airport, to undergo his initial training.

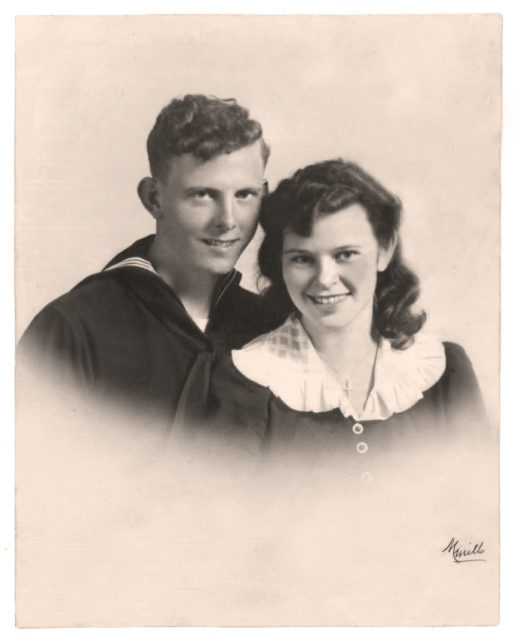

In training, he and other sailors attended dances and special events hosted by a local USO, where he soon met a young woman named Phyllis Fites; the couple married weeks later in November 1942.

“Sometime during our boot camp, these guys came down to talk to us and said they were looking for volunteers for the submarine service,” Struemph said. “I didn’t know much about it but I decided to volunteer because it meant that I would receive extra pay,” he added.

After passing the requisite tests, the recruit was sent to Groton, Conn., and was indoctrinated into his new duty assignment by learning to work on and operate the diesel engines and associated electrical systems used aboard submarines.

The next step of his journey took him to California, where he boarded a boat for Pearl Harbor. Shortly after his arrival, he received the news of the birth of his first child, which, he added, was a joyous event tempered by his exposure to the continuing efforts to recover bodies of those who perished during the attack on Pearl Harbor.

“Every morning, ambulances would line up on the piers to pick up bodies of sailors that had been killed in the attack,” Struemph said. “They had guys in the water with torches cutting the metal and removing the bodies from the compartments inside the ships that had been hit.”

Following a brief stay in Hawaii, the sailor was sent by ship to Fremantle, Australia to work aboard the USS Orion—a submarine tender that stored supplies used to perform certain repairs on damaged submarines. It was here, Struemph said, that he worked for several weeks before receiving assignment to his submarine, the USS Narwhal (SS-167).

The Narwhal, naval records indicate, returned to port in Fremantle, Australia, in late 1943 after completing several war patrols. With Struemph aboard the Narwhal as a machinist’s mate, they soon deployed for the Philippines transporting special cargo in support of the localized guerilla movement.

“We began missions of hauling Filipinos that were loaded down with grenades, radios and all kinds of equipment; they were trained to fight by the United States,” said the veteran. “We would sneak up some shallow tributary at night to avoid detection by Japanese warships. Then,” he continued, boats would come from shore to pick up the Filipinos and carry them off to fight the Japanese.”

In addition to delivering troops, Struemph recalls missions where their sub also transported soldiers and Filipinos who had escaped from Japanese imprisonment. Once everyone was aboard, the Narwhal would “back out” of the tributary and slip into waters with more depth and concealment.

“One time, our captain brought the Narwhal up a little bit and put the periscope up,” Struemph said. “He saw nothing but wings, tires and parts from airplanes floating everywhere from a battle that had taken place. He quickly retracted the periscope and we went back down and got out of there before we were detected.”

On a separate occasion, Struemph recalled, the submarine slipped through shallow waters between the islands at night and used their six-inch guns to detonate tanks used by the Japanese to store fuel.

Though the submarine experienced many narrow escapes with Japanese warships, the crew survived the war and returned to the East Coast. The Narwhal was decommissioned on April 23, 1945 and her two six-inch guns were removed for display at the Naval Submarine Base at New London, Conn.

The war in Europe ended shortly after their return stateside. However, Struemph and many of the crew of the Narwhal remained at New London for preparations to serve aboard a new submarine to be used in the planned invasion of Japan. Fortunately, he added, the war ended when Japan signed the surrender documents on September 2, 1945, resulting in his discharge the following month.

In the years following his wartime service, the veteran and his wife raised seven children and later moved from Vienna to Jefferson City, Mo., where he retired from the maintenance section of Jefferson City Parks and Recreation.

Reflecting on his service, the veteran maintains even though he and his fellow submariners frequently lived and operated under very stressful conditions, Struemph’s time in the service included many good memories, one of which made him think about the family back home awaiting his return.

“One time, while we were in Australia, some guys I was on leave with got in trouble at a bar and ended up getting locked up in the local jail,” said the veteran. “I was not involved in the scuffle but had no way to get back to the ship and there was no place for me to stay that night.” He paused, “But an Australian guy took me home to stay with his family.”

“The next morning they took me fishing and I really had a good time,” he smiled, recalling the event. “With all of the things that went on during the war, it was nice to meet good people such as them during my Navy time and to be treated as if I was just another member of his family even when mine was so far away.”