One of the most famous battles in the history of the United States Marine Corps, Guadalcanal takes its name from a small volcanic island in the west Pacific island chain. This relatively minor place on the route from East Asia to Australasia was the site of one of the hardest fought battles of the Second World War, one which was vital in turning the tide of the Japanese advance.

1. Reaching for Australia

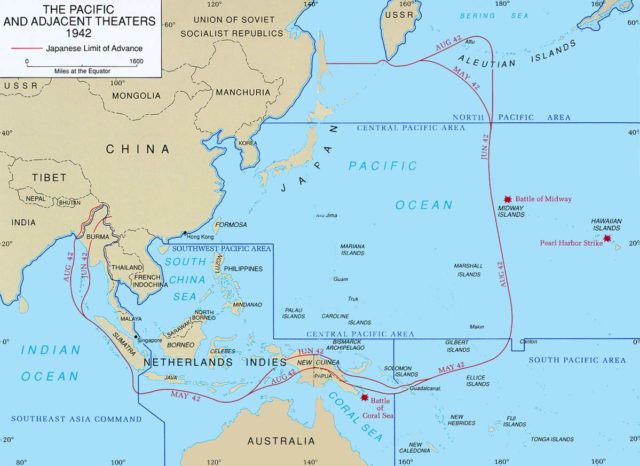

In early 1942, Japan was on the offensive. Having already occupied sections of mainland East Asia, the empire of the rising sun was expanding south along the island chain that led from there to Australia. Their agenda was a simple one – to control trade routes in that part of the Pacific, thus ensuring their own supplies and cutting off those of their enemies, in particular, China.

To do this, the aggressive Japanese army, supported by a more cautious but no less dedicated navy, aimed to conquer all the way down to Australia, removing any foothold from which the United States and European powers could strike back.

The furthest point of their expansion was Guadalcanal, the largest of the southern Solomon Islands. Owned by the British since 1893, it was occupied by the Japanese in July 1942. As the invaders set about building an airstrip, from which they could launch air defenses as well as bombing raids against Allied fleets, the need to re-take the island became urgent.

2. Bring in the Marines

The invasion of Guadalcanal was thrown together in haste, earning it the nickname “Operation Shoestring” among the troops taking part. 19,000 troops of the US 1st Marine Division under General Vandergrift took part in the initial seaborne invasion.

The operation was a tough prospect. The Marines were understrength and many lacked combat experience. Their landing craft were initially only able to provide ten days’ worth of ammunition and sixty days of fuel and food. Admiral Fletcher, fearful of placing his ships in a vulnerable position, did not provide the close support of naval and aerial bombardments for which they had hoped.

Fortunately for the Americans, the Japanese were also ill-prepared. Misinformed about events elsewhere in the Pacific, the local commander did not believe that the Americans could launch a substantial attack.

The invasion initially went well. Landing on 7 August, the Marines seized smaller surrounding islands and advanced easily from the beaches inland on Guadalcanal. The next day they took the airfield, giving them a strong base of operations with bunkers and a road to the coast.

3. War at Sea

Meanwhile, Fletcher withdrew his fleet, leaving the marines unsupported from the sea. A furious Admiral Turner sent two other fleets – one American and one Australian – to fill the gap. But the Japanese Admiral Mikawa had reached the area, and would punish the Allies for Fletcher’s withdrawal.

The fighting at sea was vital to the fate of Guadalcanal, and it began badly for the Allies. The first of five related sea battles ended with the loss of four cruisers – three American and one Australian – as well as a fifth badly damaged.

With the Japanese controlling the seas, Turner had to withdraw vulnerable supply and transport ships, leaving the marines cut off. Fletcher was ordered to return some of his ships to the area, while the Japanese increased their own naval presence, hoping for revenge for their defeat at Midway.

For three months, the Japanese retained control of the seas around Guadalcanal. The Americans and Australians could not risk advancing their ships to support the ground forces, and though they managed to stop some Japanese troops landing, many more got through. Meanwhile, Japanese ships sailed up and down the straits bombarding the Marines – a daily event that became known as the Tokyo Express.

Finally, in November, the Allies achieved the naval victory they needed. Sinking two Japanese battleships, one cruiser, and three destroyers in exchange for the loss of two cruisers and five destroyers of their own, they gained control of the seas. Now the Japanese troops were the ones without supplies.

4. The Battle on Land

Meanwhile, the battle had been raging on Guadalcanal. Vandergrift had his troops dig in around the airfield, allowing them to receive supplies as well as air support from the Cactus Air Force, the hard-pressed and hard-working air group assembled there.

The Americans became familiar with the Japanese way of war. Banzai charges, in which hundreds of men raced fearlessly at the defending guns, put the fear of Japan into the American soldiers but took a terrible toll in Japanese lives.

Dysentery and malaria swept through the marines as they struggled to hold their position. There was no possibility of retreat, and the Tokyo Express left them sleepless and on edge with its bombardments.

But increasingly regular airlifts saw supplies coming in while the Japanese received no such luxuries. Stuck living in the jungle, they too suffered from ill health, poor weather and restricted supplies.

Thousands of Japanese troops poured into attacks aimed at taking the airfield and driving out the Americans. None of them succeeded. Meanwhile, the Japanese government became increasingly wary of the death toll on Guadalcanal.

5. A Secret Retreat

From 1st to 7th February 1943, the Japanese finally withdrew their remaining forces from the island. With the seas in American hands, this had to be done covertly. Such was the secrecy that the Americans at first didn’t know that they had won and that they were alone on the island.

The Japanese withdrew 13,000 survivors. But the battle had cost them far more than this – 50,000 men lost on land, at sea, and in the air. Of even greater strategic significance was the loss of 600 planes.

The Marines lost 1,592 men of the 50,000 who eventually occupied the island. Many more Americans and Australians died at sea. Their sacrifice bought a morale-boosting victory for the Allies as the war hung in the balance, and kept open Allied supply lines through Australia.

This was the end of Japanese southwards expansion and the turning of the tide.