Erich Friedrich Michael Lackner is considered to be one of the most influential engineers of the last century. He developed a revolutionary type of concrete construction and was responsible for many projects worldwide. His legacy remains in the Inros Lackner AG construction firm, the Erick Lackner Foundation, and the Erick Lackner Award for “outstanding contributions in scientific and technical work.”

Lackner has another claim to fame, however. He was the on-site supervising engineer for the Valentin Submarine Factory in Germany. A massive facility, it took between 10,000 to 12,000 slave labourers to build it in just 20 months. These labourers were taken from their home countries and forced to work at the site. Thousands died from over-exposure, malnutrition, and summary executions, but it was never completed.

Construction began in 1943 along the Weser River in the Bremen suburb of Rekum. The Nazis already had a much bigger U-boat base in Brest, France, but it wasn’t a factory. To win the war, Germany needed to take out Britain – its only threat at sea until the Americans entered the war.

There was only one problem. Britain ruled the waves with its vast naval fleet. It also had a global empire and could call on large numbers of people and resources. But its strength was also its weakness – ships were essential to connect the empire and keep the home front supplied. Aerial raids had failed to bring the country to its knees, so Germany used submarines to disrupt Britain’s commerce and access to its crucial food supplies.

In 1943, however, America joined Britain to create a huge naval force. Worse, the British had cracked the German Enigma code and could understand secret German communications. The Allies knew where and when to attack the German submarines. In May of 1943 alone, Germany lost 42 of its existing fleet of 110 submarines.

There were already three U-boat sites in Germany – Nordsee III on the island of Heligoland, Fink II and Ebe II in the city of Hamburg, and Kilian in the neighboring city of Kiel. More were under construction, but Bremen was chosen to host two of the biggest – Valentin and Valentin II (which was never started).

The entire project was doomed from the very start, however. Despite their talent for organization and planning, the Germans really made a mess of the project. Since the Allies had already begun bombing German cities, it was decided that submarines would not be constructed in Valentin. Type XXI U-boats and would instead be built at other factories then brought to Valentin and assembled there.

The idea behind this complicated scheme was to ensure that no single bombing raid could take out U-boat production. It was also hoped that the Allies would be kept guessing as to where they were being made and where they were being assembled – bearing in mind that the Germans didn’t know that their code had been cracked and that the British were aware of their plans.

Valentin was designed and overseen by the Organisation Todt – the civil and military engineering arm of the Third Reich which made use of prisoners, some of whom came from the various concentration camps. Edo Meiners was in charge of the project, but Lackner was in charge of the site and the day to day running of the project.

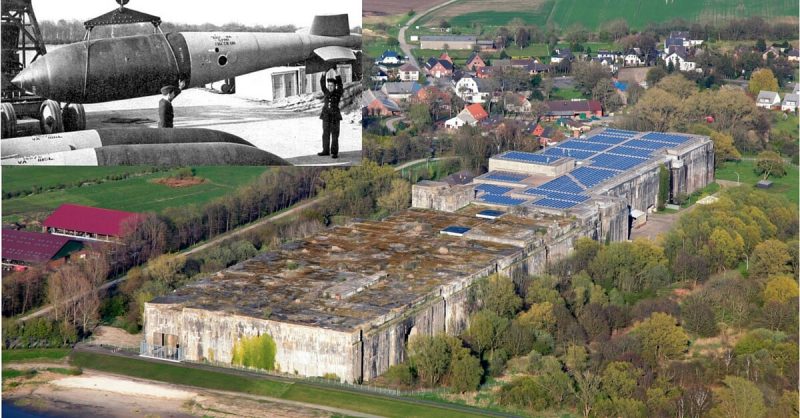

The facility stood between 74’ to 89’ tall, stretched 1,398’ long, and was 318’ at its widest point. To protect it from aerial bombardment, its walls and roof were 15’ thick. In time, parts of the roof were further thickened to 23’. By the time they were 90% done in March 1945, some 500,000 cubic meters of concrete was used for the project, while the human cost was much higher.

Valentin was to be operated by the Bremer Vulkan shipyard, which would assemble the U-boats in 12 bays, supported by workshops and storerooms. Once built, they would be tested for leaks in a 13th bay which could be flooded with water. If they passed, they would then be released into the Weser for service. Using more slave labor, the facility was expected to produce a fully functional submarine every 56 hours.

Seven camps were built to house the slave laborers, though others were kept at the Bremen-Farge concentration camp (part of the much bigger Neuengamme concentration camp complex). Others were kept at a naval fuel oil storage compound, while some were put in an emptied underground fuel tank.

Besides French, Polish, and Russian POWs, German civilian criminals and others deemed “undesirable” were also put to work as slave labourers. The workers did 12-hour shifts and more with little food and medical care under the careful watch of SS soldiers. Those too sick or too slow were executed. This brutal policy of killing prisoners created labor shortages by 1944, greatly slowing down production.

It’s estimated that some 6,000 people died on the project – a figure which doesn’t include Russians and Poles since their deaths were not recorded. To the Nazis, they were sub-human and not worth mentioning. Most fatalities occurred in the “iron detachments” – among those responsible for moving girders of iron and steel.

The Allies knew about Valentin not just because of German communications, but also because they weren’t blind. When night fell, all towns and villages had to shut off their lights, but not Valentin where construction took place 24/7. Rather than put a stop to it, the Allies decided to let it continue because it drained limited German resources. Besides, they were very successful at destroying German supply lines.

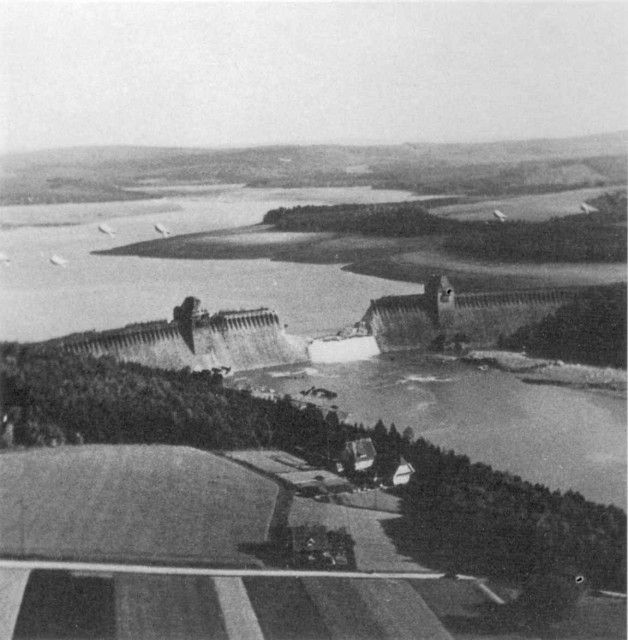

In 1943, the Allies experimented with a new weapon called an earthquake bomb –which could create maximum damage with fewer bombs. These were considered for use on several German dams from May 16 to 17, 1943 as part of Operation Chastise but ultimately the bouncing bombs were used to destroy the dams and drown villages and towns in the Ruhr and Eder valleys.

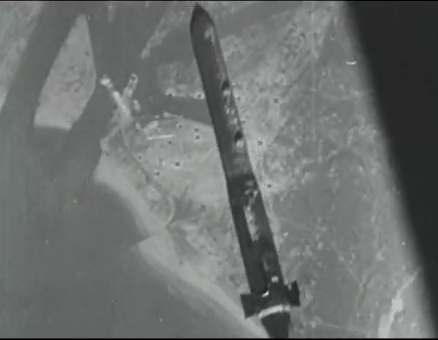

Valentin neared completion in 1945, so the Allies finally attacked on March 27. Two Grand Slam quake bombs blew holes through the roof, while others destroyed the nearby supporting facilities. On March 30, the US Eighth Air Force launched their Disney bombs to finish the job, but only one hit the facility. By this date Valentin was never going to produce any submarines because the Nazi regime was on the verge of defeat.

The place was finally evacuated in April. Its surviving prisoners were put on the SS Cap Arcona which was sunk by the British Royal Airforce on 3 May 1945. Of the 5,000 POWs aboard, only 350 survived. The British Army’s XXX Corps captured Bremen at the end of April 1945.

In 2011, the Bremen Regional Authority set aside $3.8 million to turn Valentin into a museum to remind the current generation about the cruel treatment of the slave labourers and prisoners at the site. It will serve as a reminder to future generations of the cruelty of the Nazis.