“Landed. Eliminated Germans. F#$%^d off.” Anders Lassen, a Dane from an aristocratic background, was an adventurer and one of a kind warrior.

He served in various iterations of the British special forces during the war, the first being No. 62 Commando, a special unit within the Commandos better known as the Small Scale Raiding Force (SSRF).

In 1943, he joined the Special Air Service, the famed “SAS,” in their branch of amphibious warriors, the Special Boat Section (SBS). To qualify for any of those units, one had to be the best of the best.

All of those units included more than a handful of outlandish characters, many of whom would not have succeeded in more conventional units.

It is the opinion of many historians that others of the SBS and the SAS should have received the Victoria Cross (VC), Great Britain’s highest citation for bravery, but it was likely that an institutional prejudice against these more unconventional units prevented it.

For example, that prejudice was probably the case with Lt. Colonel Blair “Paddy” Mayne of the SAS, who was among the most awarded men of any country during the war.

Lingering doubts about his character, since he was a heavy and violent drinker in off-duty hours, probably prevented him from being awarded the Victoria Cross.

Anders Lassen was born in Denmark in 1920, and like many other freedom loving people from the nations overrun by the Nazis, fled to England to continue the fight.

In the first days of the war, Churchill ordered the formation of units which would raid German-held territory in order to keep the Germans off balance, let the people in those countries know Great Britain was still in the war, and get intelligence needed by the Allies.

Churchill named these units “commandos” after the swift-moving raiding forces of the Afrikaaners during the Boer Wars.

In fact, it was one of those units that had captured Churchill during the conflict. He was impressed by their abilities, their esprit de corps, and the havoc they wrought behind British lines.

Some of the early Commando units were made up of foreigners from the occupied countries. There were Norwegian, French, Belgian, and Danish Commando units. There was also No. 62 Commando, made up of men from all of these countries, as well as British soldiers.

No. 62 Commando was under the command of the Special Operations Executive, or “SOE,” the ultra-secret irregular warfare unit which controlled agents behind the lines and carried out missions too sensitive to be made public or even known to many in the British military establishment.

SOE’s charter from Churchill was famously “Set Europe Ablaze,” and to do that, SOE needed men and women that didn’t mind getting their hands dirty and breaking more than a few rules.

Anders Lassen was one of them. He came from a background of unusual and brave people. His father famously summoned his Rolls Royce in front of the Hyde Park Hotel with a hunting horn on a pre-war visit.

His German cousin, Axel von dem Bussche, was involved in two bomb plots against Hitler, and was one of the only officers to have survived the war.

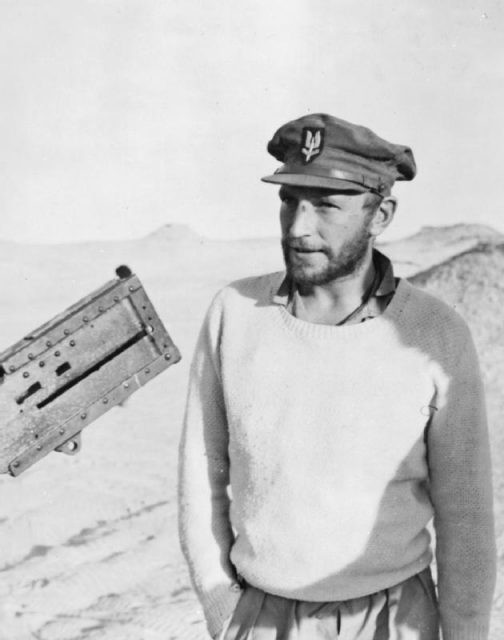

Respect for authority simply because they were in authority was not part of Lassen’s make-up, nor that of many of the men in the SOE/SSRF/SAS. A famous story with some truth in it has Paddy Mayne punching out a superior officer. Others in the SAS wore whatever they wanted, including full beards.

One of them was Lassen. An officer once gave his men a dressing down about it: “What would the Germans think if they discovered your dead bodies on the battlefield–unshaven??” The men simply walked away.

On another occasion, Lassen sent in his after action report which read “Landed. Eliminated Germans. F#$%^d off.”

One reason these men could get away with this was because they were protected by Churchill, but the main reason was because they were good. Lassen saw action in Northern Europe, Crete, North Africa–he was part of the ill-fated Rommel raid to capture or kill the German Field Marshal–Greece, and Yugoslavia.

One of his most famous actions, and one not known to the High Command, but to Churchill and a handful of his cronies was a raid on the Spanish island of Po, off the coast of Guinea, Africa.

This raid remained secret for years, and rumors of it were denied for just as long, for the Spanish were neutral but leaned towards the Axis.

Churchill was leery of pushing Spain into the Germans’ arms, but the Germans and Italians were using Po as a base for disguised commerce raiders that were preying on Allied ships bringing vital supplies to England.

These raiders were trawlers and tankers that had had most of their extra weight removed, and while they still presented the outline of a commercial ship, they were armed to the teeth. They also flew a false flag, and in the first part of the war they lured many British and other ships in closer, and to their deaths.

The SSRF was tasked with either disabling or capturing the Italian and German ships at the islands’ port. Had Spain not been sheltering the forces of their enemy, then the British would not have had to mount the raid–so Churchill’s thinking went.

In theory, a neutral port was open to everyone including the British, but Churchill had no illusions of that ever happening. He wished to send a message not only to the Axis, but to Spain: “Don’t be drawn into this. We can hit you too.” The operation was code-named “Postmaster.”

There were two parts to the plan. First, an SOE agent on Po would approach the wife of a German diplomat on the island and persuade her to throw a wild cocktail party for the Axis officers on shore. This would take the commanders and much of their crew away from the vessels.

Second, Lassen and his men would approach the islands in civilian dress, aboard the sailing vessel Maid Honor registered in Sweden – they were taking a pleasure cruise under a neutral flag.

On the night of 14-15 January 1942, the SSRF men on Maid Honor boarded two British tugboats which had made their way from nearby Lagos, Nigeria, which was a British colony at the time.

The tugs were carrying more SSRF men, SOE and British regulars from Nigeria. With lights out, the men transferred to the tugs. As they approached the port at Po, the men of the SSRF switched to their Falboat kayaks and approached the German and Italian commerce raiders Duchessa d’Aosta and Likombo.

The local guards on Likombo jumped ship when the raiders with their darkened faces and machine guns suddenly appeared on the deck of the ship.

The commandos then blew the iron anchor chains holding the ship in place and waited until the Duchessa d’Aosta was also in British hands–which it was shortly, for the Italian crew was in no mood to fight commandos in the middle of the night. The tugs then put each vessel under tow and left the harbor.

Once they made it out to sea, the British put out a radio signal that they were claiming two prizes on the high seas – ships which somehow must have drifted out of port since there was no crew on either vessel.

Everyone knew it was a lie, and the Spanish protested at the violation of their neutrality, but there was not a thing they could do about it.

Lassen and his men received citations for this raid, though it was not widely broadcast because of its “illegal” nature, and Lassen’s reputation grew.

In early 1943, the SSRF was disbanded and many of the men were folded into the SAS. Lassen joined their amphibious unit, the Special Boat Service (SBS), which operated small scale raids and reconnaissance from the sea.

Like many of the SAS leaders, Lassen was informal. He knew that his men would carry out his orders because they were the best and they respected him. Like David Stirling, who had founded the SAS, and others, Lassen did not order his men to do anything that he would not do himself.

Lassen was also a notorious partyer, much like his SAS comrade “Paddy” Mayne. On leave, he was on vacation–not leave.

He did what he wanted, when he wanted, with who he wanted. He was willing to put his life on the line in the most dangerous missions, so he and his men would blow off some steam when they had the chance.

For example, when Athens was liberated in 1944, he stole a jeep to go carousing in. Someone then stole it from him. No matter–shortly thereafter, American forces showed up, so Lassen stole one of their jeeps.

He drove it up the stairs of his hotel, into the cargo elevator used for luggage, and up to the suite he occupied.

Later during Lassen’s stay in Athens, he was “entertaining” a local woman, but his men were partying too loud nearby.

He went out into the hall wearing nothing but his boots, and asked them “Chaps, can’t you let your CO s***w in peace?” Of course, his men loved him all the more for it.

Sadly, Lassen did not survive the war. With just about a month before the Nazis surrendered, Lassen and his men were tasked to neutralize an Italian and German stronghold on the shores of Lake Comacchio in northern Italy.

Unfortunately, they were detected by guards in nearby blockhouses and challenged. They tried to pass as local Italian fishermen, but that did not work, and they were soon under fire.

The situation was dire: Lassen and his men were on a causeway with water on both sides. Soon they were under fire from the men they had bypassed, as well as others in front.

Lassen charged ahead with a sub-machine gun and a satchel of grenades. He took out one blockhouse single-handedly and advanced on another, under covering fire from his men. He soon overran this position, killing two men and taking two prisoners.

By this point, Lassen’s men had caught up with him, and they began to fire on a third enemy position. Again Lassen advanced alone, and took out this position as well. Germans inside began yelling “Kamerad,” offering their surrender.

Just then a position to his left opened up with an MG-42 machine gun, and mortally wounded the Dane. While he was falling he tossed another grenade at that position, which wounded some of its occupants and allowed his men to capture that position as well.

Read another story from us: 8 Men Who Led Britain’s Crazy & Amazing Covert Operations of WW2

His men wanted to evacuate him, but Lassen refused. The unit was still under heavy fire, and he knew that if his men stopped to help him, they too would become casualties or corpses. He died shortly after refusing to be carried out. In 1945, he was posthumously awarded the VC. He is buried at the Argenta Gap War Cemetery in Italy.