General Joseph Stilwell, widely known as Vinegar Joe, had one of the strongest personalities of WWII. As American commander in Burma, he showed incredible insight into the challenges of war in that region. His stern attitude was at times his greatest asset; at others, it was his biggest flaw.

The Tough Guy

Stilwell earned his nickname and his tough guy reputation long before WWII.

From early in his career, Stilwell’s short temper and colorful language made him stand out. He had no patience for inefficiency or stuffiness. It led him to have a deep disdain for the British he worked with in Burma, an attitude that caused problems.

He was also a smart, capable leader. That was why he was in a position of great responsibility.

Early Years

A West Point graduate, Stilwell was commissioned in 1904. Aggressive, highly professional, and gifted with languages, he served in the Philippines and China. There he earned a reputation as someone willing to speak his mind about inefficiency. Returning to America, he became an instructor at West Point before serving in WWI, where he saw the fierce fighting of the last great German push.

The Chinese Expert

After the war, Stilwell applied for a post in China. He arrived there in 1920. Although he returned to the US for officer training and other assignments, he spent much of the interwar years in positions in China.

There, he scorned the life of leisure and cocktail parties that many expatriates enjoyed. Instead, he acted as a supervisor on public works before traveling the country.

He saw first-hand the suffering of the Chinese people. He watched as first civil war and then Japanese invasion tore the country apart. All sides showed a disdain for human life. He witnessed the Rape of Nanking in 1937 when the Japanese massacred 40,000 civilians.

Through his brave and diligent information gathering, Stilwell became one of America’s top experts on China. He also developed a dislike of many of those involved, especially the Japanese.

Settling in Amid Setbacks

Following the attack on Pearl Harbour, America and Britain joined in the fight against Japan. In early 1942, Stilwell was appointed to take charge of American forces in Burma.

A British possession, Burma was invaded by the Japanese in January 1942. The British were rapidly pushed back and Chinese attempts to intervene crumbled before Japanese advances. For months, the British fought a desperate retreat through the jungle.

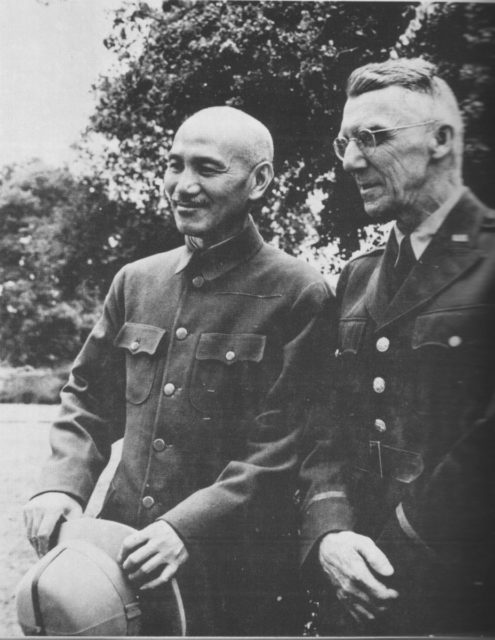

Stilwell commanded the US and Chinese forces in Burma. Chiang Kai-Shek, the Chinese Nationalist commander, gave the Americans ostensible command of some of his troops.

Although focused on supporting the British and Chinese withdrawal, Stilwell led Chinese forces in a counter-attack that beat the Japanese at Tounggyi. It showed that, with good command, they could achieve a great deal.

Handling the Chiang Kai-Shek Problem

Stilwell found many problems with his Chinese troops. They were poorly equipped. Their commanders lacked boldness and courage. Supplies were not properly organized. The main recurring problem, however, was Chiang Kai-Shek.

He frequently failed to live up to his promises and countermanded orders from Stilwell. He played politics, threatening to withdraw from the campaign if America did not give him more supplies.

Stilwell put a tremendous effort into negotiating with and managing Chiang. It was an experience that embittered both men. With his strong character and local knowledge, though, Stilwell showed he was the right man for the job.

Strategic Brilliance and Playing Politics

Stilwell was a sound military planner. He produced a strategy to tackle the Japanese through a simultaneous attack by all Chinese forces. It would give their allies a chance to advance, but with Chiang involved, there was no chance of it happening.

Stilwell was part of meetings between Roosevelt, Churchill, senior Allied commanders, and Chiang. The Chinese demands and duplicity were apparent, but the Allies had to work with him. Stilwell was offered another posting to defuse his frustration, but he stuck with the job.

Advances

Despite constant bickering at the top, the Allies made progress in Burma. A Japanese counter-attack in early 1944 was a setback, but Stilwell was determined to push back.

He planned to advance south on the airfield at Myitkyina before linking up with the Burma Road. Substantial advances were made, including the capture of supplies at Tanaka by General Sun, a Chinese general acting decisively despite Chiang’s orders.

Myitkyina and Mogaung

The towns of Myitkyina and Mogaung were crucial to Stilwell’s strategy. His frustration and the yes-men surrounding him blinded Stilwell to the nuances of his situation.

Given command of Merrill’s Marauders, an elite irregular force, he flung them into an ill-supported frontal assault on Myitkyina. It wasted their talents and caused enormous losses. The Chindits, British irregulars put under Stilwell’s command, suffered from similar misuse. In his hurry to out-do the British, Stilwell made tactical errors and failed to credit the Chindits when they captured Mogaung.

His bull-headed determination was turning into a flaw. When one of the Chindit commanders, Michael Calvert, challenged him, Stilwell showed another side to his personality. At first arguing with Calvert, he changed his mind deciding he liked Calvert’s willingness to challenge him. He had found a like-minded Brit at last.

A Bitter End

As the Allies advanced through Burma, problems with Chiang continued. In response to the Chinese commander’s obstructions, Stilwell delivered a blunt message from Roosevelt. In response, the Chinese demanded Stilwell’s removal; a demand the Americans could not afford to ignore.

Despite being honored for his service, Stilwell was left bitter. He had been unceremoniously dismissed and was told not to discuss the China problem with anyone, particularly the media.

Stilwell served until the end of the war and was present at the Japanese surrender. He died on October 12, 1946, from stomach cancer.

Stilwell was a brilliant but difficult commander caught in one of the most challenging posts of WWII. It was a shame that, in the end, politics prevented him from achieving all he could have done.

Source:

David Rooney (1999), Military Mavericks: Extraordinary Men of Battle.