In 1943, a US Navy destroyer engaged a Japanese submarine during the Solomon Islands Campaign. What should have been a skirmish between equals turned out to be a one-sided affair, however, because the Americans had a deadly weapon at their disposal, one that allowed them to sink the sub and send its crew to a watery grave.

And what, you ask, was this devastating weapon? Potatoes.

The USS O’Bannon (DD-450) was a Fletcher-class destroyer and the second one named after Lieutenant Presley O’Bannon, a decorated war veteran of the First Barbary War (1801 to 1805). Built in Maine in 1941 and launched the following year, it went on to become the most decorated American destroyer during WWII. By the end of its career, it had earned 17 battle stars and a Presidential Unit Citation.

Our story’s background begins in 1942 as the O’Bannon was making its way to the island of Guadalcanal. The Japanese had completed an airbase there in April of that year and named it Runga Point. Since the Allies were trying to dislodge the Japanese from the Solomon Islands, they took Runga Point four months later in August and renamed it the Henderson Field. The Japanese were rather upset about that, of course, and wanted it back.

Fast forward three months. The O’Bannon was providing escort duty for a fleet of supply ships headed toward Henderson Field when a Japanese submarine surfaced to take them out. The O’Bannon fired at the sub, forcing it to stay under till the convoy had passed. On November 12, the convoy was attacked by 16 Japanese torpedo bombers, 11 of which were destroyed, four by the O’Bannon.

But the Japanese had put too much into Henderson Field and sent over a larger convoy made up of a light cruiser, two battleships, and 14 destroyers. If they couldn’t take the airfield back, they intended to destroy it so it couldn’t be used against them. The Allied fleet, composed of the O’Bannon, two heavy cruisers, three light cruisers, and eight destroyers were outnumbered.

The two sides met at Iron Bottom Sound (so named because of the many ships sunk there) on the morning of November 13. The O’Bannon damaged the battleship Hiei so badly that she had to be scuttled the next day. By day’s end, the Allies had won, and Henderson Field remained theirs for the remainder of the war though the Japanese kept their grip on other islands.

The O’Bannon, therefore, spent the rest of the war helping to bombard those remaining Japanese positions, as well as providing escort duty for ships that supplied the Allied-held islands. It was during such a run, the following year, which it found itself having to use its secret weapon.

On the evening of 4 April 1943, the Destroyer Squadron TWENTY-ONE (DesRon 21), a fleet of destroyers which included the O’Bannon, had shelled Japanese bases in the New Georgia area. Early the following morning, they were returning to base at Nouméa, New Caledonia, when the O’Bannon’s radars picked up a large Japanese submarine.

It was cruising along on the surface, seemingly oblivious to the oncoming American ship. Commander Edwin R. Wilkinson ordered the O’Bannon to speed up and ram the sub, but as they got closer to it, caution won out. What if it was a minelayer? If it was, then ramming it would be suicide as the resulting explosion would destroy the destroyer.

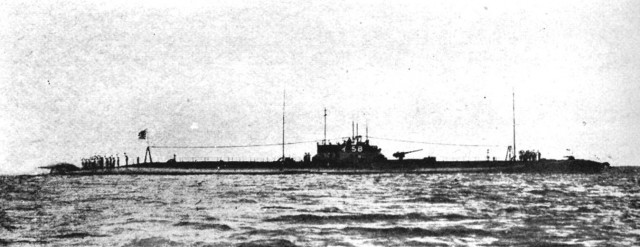

But the ship had already built up a momentum. So they turned the rudder so hard that the O’Bannon groaned while a large wave surged ahead to bash at the sides of the cruising sub. The maneuver worked. Instead of hitting the Ro-34, they banked sharply and found themselves sailing parallel to it.

Still no response from the Japanese. Looking over their railing, the Americans found out why. On the sub’s deck were sailors dressed in dark shorts and blue hats. And all of them were asleep.

The Allies’ fascination with the sleeping Asians couldn’t last, of course. First one, then another, and finally, the rest woke up. Pandemonium broke out as the Japanese stared up at the gawking enemy looming over them.

The American sailors wanted to open fire, but they had no guns among them. The Japanese also wanted to shoot, but they, too, were unarmed. According to Ernest A. Herr (who was aboard the O’Bannon that day), silence descended as the two sides ogled each other wondering what to do next. Military protocol didn’t cover such situations, apparently.

That, too, couldn’t last. The Ro-34 was armed with a 3” deck gun, and once the initial shock had passed, the captain realized that it might be a good time to use it. Although the O’Bannon also had deck guns, it was too close to the sub and perched too high to do any good.

The Japanese ran toward their deck gun. The Americans ran to their storage bins. No guns or grenades.

Only potatoes. Desperate, they reached in and threw as many as they could at the Japanese below, hoping to keep them away from their deck gun, but knowing it was a useless gesture. They were wrong.

The Japanese panicked. The brave among them picked the potatoes up and threw them overboard. Others threw them back at the Americans who threw them back at the Japanese.

It took the Americans a while to realize why the Japanese were so panicked – they probably thought that the potatoes were hand grenades. To this day, Herr isn’t sure why the Japanese were so afraid of the potatoes, but he’s grateful they were because they never made it to their deck gun.

The O’Bannon, meanwhile, used the potato war to distance itself from the sub. It got far enough away to use its deck guns, taking out the Ro-34’s conning tower. The sub dived, so the destroyer surged forward again, passing overhead and dropping depth charges that destroyed the Japanese vessel.

When the Association of Potato Growers of Maine heard about the incident, they sent the O’Bannon a plaque to commemorate the event. She went on to serve in the Korean War and when she was decommissioned in 1970, the plaque was still aboard.