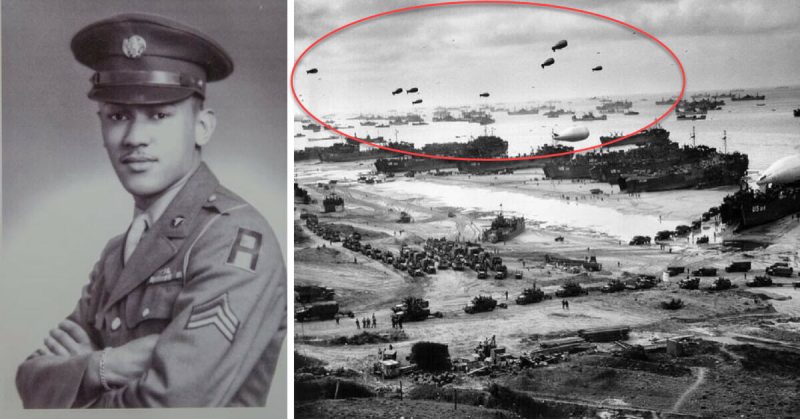

When most think of D-Day, they imagine a mass of men storming the beaches of France in a hail of bullets. Though this image is accurate, there were also the barrage balloon brigades who were denied recognition.

Barrage balloons were a deterrent against enemy planes. Tethered to the ground with metal cables, they prevented planes from flying too low for fear of either having their wings cut off or being blown up, since some balloons had explosives attached to their wires.

They served another function. Surface-to-air batteries couldn’t effectively target low-flying high-speed planes, so balloons forced them to fly higher – putting them within range of ground weapons. Even then, the balloons had one final purpose. Because planes flew even higher to avoid balloons and surface fire, their ability to accurately hit targets on the ground was reduced.

And that’s why they were valuable during the Normandy landings on June 6th, 1944. If you look at pictures of that day, you’ll see lots of them overhead. Less well-known, however, is who put them there – which also explains the lack of recognition.

The 320th Barrage Balloon Battalion (VLA – for “very low altitude”) was a 621-assault force responsible for those hydrogen-filled blimps. Among them was a remarkable man named Waverly Bernard “Woody” Woodson, Jr.

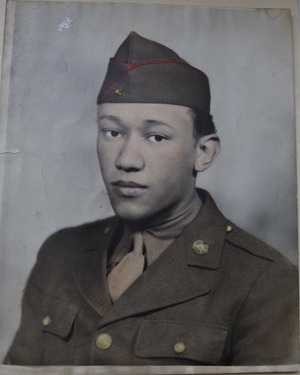

Woodson was a 20-year-old pre-med student at Pennsylvania’s Lincoln University when America joined WWII in 1941. Instead of waiting to be drafted, he dropped out in his second year to enlist on December 15th, 1942.

He passed an exam that qualified him for the Anti-Artillery Officer Candidate School, but no positions were available for him. The army did need medics, however, so they sent him to Camp Tyson in Tennessee to join the 320th Barrage Balloon Battalion (VLA) – an all African-American unit under white officers.

Though used to discrimination, Woodson was shocked when he crossed the Mason-Dixie line. Getting there by train, his group had to close the curtains of their cars.

It wasn’t to protect the white passengers from the sight of blacks, since there was segregated seating. It was to protect the blacks from getting shot at by whites outside.

Even more amazing was the restaurant service. Thousands of German POWs were on US soil – many of whom worked on farms and were paid because of the Geneva Convention.

Though officially enemies, these POWs were allowed to eat in the restaurants. And the black men in uniform? Nope. They were allowed to eat… so long as they did it outside.

Image Source: Linda Herieux <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=e73e26_qcQ8>

Their arrival in Scotland was a shock. The 320th were the first American troops to arrive and were treated like heroes. Some Scots even invited a number into their homes. It was the same throughout the rest of Britain, but it couldn’t last.

As more white Americans arrived, they tried to bring their attitudes with them. On June 24th, 1943 British military police stopped four African-Americans from entering a bar in Bath, Somerset. They didn’t agree with segregation, but they were under pressure from US officials and white GIs to practice it.

In response, the British rioted… against the police. The next day, the Bath Chronicle and the Weekly Gazette expressed outrage at the treatment of the African-Americans.

The US responded by court-martialing 32 of their own black soldiers. Willie Howard, a member of the 320th, later said that, “Our biggest enemy was our own troops.”

Image Source: Linda Hervieux <http://www.lindahervieux.com/the-320th-blog/2015/9/3/waverly-b-woodson-jr>

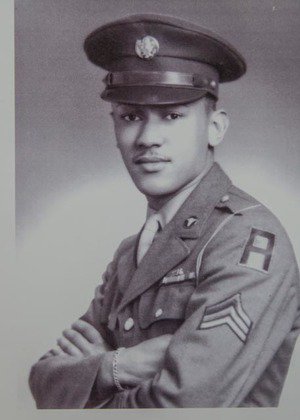

The 320th was the only African-American unit who took part in the D-Day landings. Woodson was in a landing craft tank (LCT) with four other medics who watched the first wave storm the beach two hours before. His turn came at around 9 AM.

It was a nightmare. The dead floated in the water, while the wounded cried out for help. Woodson wanted to do just that, but megaphones blasted orders to ignore the wounded and get to shore.

They did so… on a landmine. So now their motor was down. A shell hit the right side, killing some men, including the gunner. Another shell took out a jeep and the four men inside.

Woodson crouched beside the medical jeep when another explosion hit, sending shrapnel into his buttocks and thigh.

Image Source: Mariegriffiths CC BY-SA 3.0

The LCT’s ramp hit the beach. Its tank rolled off with the survivors running behind it for shelter. Despite his wounds, Woodson staggered after them as bullets whizzed by.

The other medics ran toward a rocky outcrop that provided shelter from bullets. Grabbing a tent from the water, Woodson dragged it to the shingle when another explosion made him turn. The tank was now on fire.

The Geneva Convention decreed that medics wearing Red Cross armbands shouldn’t be shot. Unfortunately, the German soldiers didn’t get the memo.

So despite enemy fire, Woodson dragged men out of the water, revived four half-drowned ones, took out bullets, closed wounds, and even amputated a foot. No one cared about the color of his skin, then.

At around 3 PM on June 7th, Woodson finally passed out – after working for about 30 straight hours and treating some 200 men.

Omaha and Utah beaches covered such a vast area, that the 320th were spread out thin. So though a balloon required four to five men each, some only got two. To become faster, more efficient, and improve their chances of survival, the battalion invented lighter equipment that allowed one man to carry a balloon wire drum.

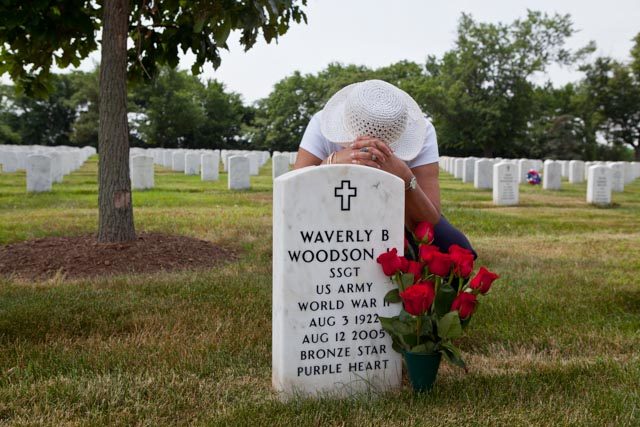

The 320th were later sent to Hawaii in 1945 for training in the Pacific when the war ended. General Dwight D. Eisenhower commended them highly, while General John HC Lee wanted Woodson to have the Medal of Honor.

It never happened. All African-Americans who served in WWII were glossed over with minor awards. As for Woodson, he got a Bronze Star and a Purple Heart.

Image Source: Linda Hervieux <http://www.lindahervieux.com/the-320th/>

In 2009, however, France gave the Legion of Honor (its highest military and civilian award) to a foreigner. That man was Corporal William Garfield Dabney – an African-American who served in the 320th.

This spurred American journalist Linda Hervieux to do some digging. The result was her first book – “Forgotten: The Untold Story of D-Day’s Black Heroes, at Home and at War.”

Woodson left us in 2005, but if you’d like to get him that Medal of Honor he deserves, please sign his family’s petition at http://petitions.moveon.org/sign/congressional-medal-wwii.

You can also find out more about America’s other forgotten black heroes by visiting Herviuex’s site at http://www.lindahervieux.com/.

Image Source: <http://www.lindahervieux.com/the-320th-blog/2015/9/3/waverly-b-woodson-jr>

Except where otherwise stated, all pictures © Linda Hervieux, used with permission.