“Those guys in WWII never really talked about their service…at least the ones that I knew.

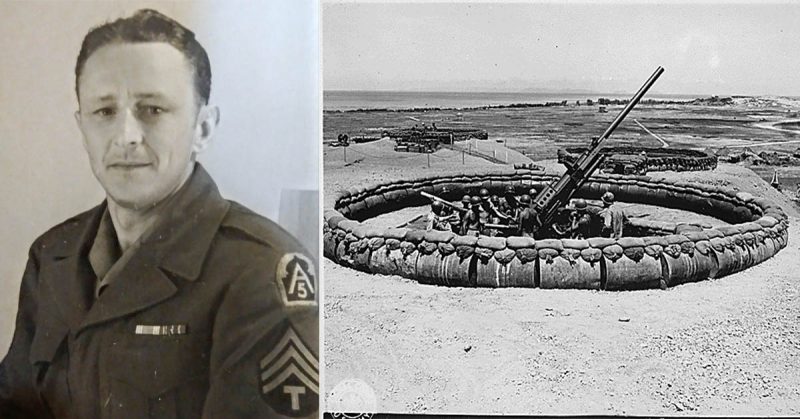

For an account of a veteran’s military service to survive the passage of decades, it often needs a conduit through which to be shared. Loretta Raithel of Russellville had suspicions that once her brother-in-law, Virgil O. Shikles, passed away at only 55 years old, followed by the death of his son in 2004 and his wife several years later, there was no one left to preserve his legacy of service in World War II.

“When my sister passed in 2012, [Shikles’] military records and photographs could have easily been discarded, but I have hung on to them to help preserve the memory of what he had done in the war,” Raithel said, sifting through papers related to the military service of her brother-in-law.

Virgil Shikles was born October 27, 1913 and raised near the rural community of Enon as the second oldest in a family of six children. Records indicate the 26-year-old registered for the military draft in Washington, Missouri on October 16, 1940, more than a year prior to the attack on Pearl Harbor.

According to the National Archives and Records Administration, “President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed the Selective Training and Service Act, creating the country’s first peacetime draft and officially establishing the Selective Service System.” The act required all males between the ages of 21-36 to register during the first draft registration held on October 16, 1940, the date listed on Shikles’ registration document.

At the time of registration, he was employed by the former Missouri Pacific Railroad headquartered in St. Louis. In his position as a “trackwalker,” he was responsible for walking sections of the railroad’s track system to examine the condition of joints, rails and ties, ensuring there was no damage that could cause a train accident.

Statistics from the National World War II Museum state, “By the end of the war in 1945, 50 million men between eighteen and forty-five had registered for the draft and 10 million had been inducted in the military.” One of those drafted, Shikles received his own call in early 1942, approximately six weeks after the U.S. declared war.

The “Enlisted Record and Report of Separation” for Shikles shows he was inducted into the U.S. Army at Jefferson Barracks in St. Louis on January 21, 1942, beginning a period of military service that would extend nearly four years.

As the weeks passed, Shikles was assigned to the 401st Coast Artillery (CA) and began training at Camp Haan, California—a military reservation established in 1940 to serve as a Coast Artillery Antiaircraft Replacement Training Center. In April 1942, the 401st CA was re-designated the 401st Antiaircraft Artillery (AAA) Gun Battalion.

The battalion was equipped primarily with M1 90mm antiaircraft guns which were towed behind vehicles. Shikles trained as a radar crewman, learning to assemble and disassemble the battalion’s mobile radar equipment in addition to operating the radar to detect and locate possible aerial threats. The battalion would participate in desert maneuvers at Camp Young, California.

Shikles and the 401st AAA Battalion went on to train at Camp Pickett, Virginia, before “boarding an LST in April, 1943, for an unknown destination overseas,” reported the July 21, 1944 edition of the Folsom Telegraph (Folsom, California). The paper further noted the battalion landed at Arzew—a port city in Algeria—where they were attached to the Fifth Army.

Following a short period of training, the battalion boarded LST’s (Landing Ship, Tank) in early August 1943 bound for Tunisia, met up with a convoy of American troops and then sailed for Sicily. Weeks later, they were sent to the Italian front, where they began defending supply depots, roads, bridges, airfields and critical military installations.

The battalion continued to move up with the front lines and, on May 1944, “the whole Italian front exploded into action and the big drive for Rome was on,” noted the November-December 1946 edition of the Coast Artillery Journal.

The journal further listed the challenges encountered by U.S. forces during this campaign: “Enemy aircraft flew in low from several directions toward the points of attack making 90mm fire extremely difficult. Radar control was often unsatisfactory due to terrain interference and large quantities of [chaff] dropped by the Germans.”

By the time the war in Europe ended on May 8, 1945, Shikles had earned five Bronze Stars for his participation in five major campaigns in Italy. The 401st AAA Battalion remained overseas until boarding ships bound for the United States in October 1945.

Within days following his return, Shikles took a train to Jefferson Barracks, where he processed out of the U.S. Army and received his discharge on November 6, 1945, having served more than three years and nine months in military uniform.

“After he returned home, he married my sister, Evelyn Scott, in February 1946,” said Loretta Raithel. “They later moved to Kansas City, Kansas, and raised a son, Gary.” She added, “He then went to work for General Motors until he became so ill with Parkinson’s disease that he was no longer able to maintain his employment.”

The World War II veteran passed away on August 12, 1969 at the age of fifty-five. His son, Gary, who later served with the U.S. Navy during the Vietnam War, also died from complications related to Parkinson’s in 2004; he was 56 years old and had no children. Like his father, he was laid to rest in Enloe Cemetery near Russellville.

“All of my brother-in-law’s records went to my sister and when she passed away in 2012, I made sure to hang on to them because they would have disappeared since his family is all gone,” said Raithel.

She continued, “Those guys in WWII never really talked about their service…at least the ones that I knew. It’s important to save their stories, and those of other WWII veterans, so others can appreciate what they went through during the war.”

Jeremy P. Ämick writes on behalf of the Silver Star Families of America.