Adolf Eichmann, one of the chief architects of the Holocaust, became an infamous figure after his heavily publicized trial and execution in Israel in 1962. Eichmann joined the Nazi Party and the SS in 1932 while he was living in Austria. In 1933, the National Socialist German Workers’ Party (NSDAP) was banned in Austria following civil war clashes between the State and the Social Democratic party in Linz. Most of the Austrian members emigrated to Bavaria after the ban, to the heartland of the NSDAP.

The following year he was accepted into the ranks of Sicherheitsdienst, the SD or the Nazi Security Service, where he was appointed the head of the department responsible for Jewish affairs—especially emigration, which the Nazis encouraged through violence and economic pressure. He became a notable figure in the Reich, mainly for his skills in the organization of transport and logistics needed for the mass deportations of Jewish people.

Eichmann, together with his staff, planned how to run the ghettos; his pre-war occupation concerning the deportations was mainly concentrated on drawing plans for the future Jewish reservations, as the Jews were to be banished, first to Nisko in southeast Poland and then finally to the island of Madagascar in the Indian Ocean. None of these plans were carried out after it became evident that the war effort was not going as planned.

In January 1942, the Eastern Front was crumbling, and it was obvious that the Nazis were not going to hold the Soviets back much longer. Meanwhile, Eastern Europe held most of the displaced Jews, and the question arose – was it time to intensify the extermination before these territories fall within the grasp of the Soviet Union? On that occasion, a conference was summoned in Wannsee, on January 20th, 1942.

The conference was headed by Reinhard Heydrich, Chief of the Reich Main Security Office. The main reason the conference was held was that Hitler, after the US entered the war, decided to conduct the Final Solution during the ongoing conflict and not afterward, as had been planned (after the German victory, which wasn’t imminent in 1942).

The Wannsee conference was meant to co-ordinate the execution of the Holocaust, and Eichmann’s was the most important role. The administrative leaders of the regime were all given tasks to bring about the extermination of the Jewish population in Europe in a very short period of time.

This demanded precise planning. In preparation for the conference, Eichmann drafted a list of the numbers of Jews in various European countries and prepared statistics on emigration. Eichmann attended the conference, oversaw the stenographer who took the minutes, and prepared the officially distributed record of the meeting. In his covering letter, Heydrich specified that Eichmann would act as his liaison with the departments involved. Almost immediately after, Eichmann ordered large-scale deportations to begin.

Death camps like Belzec, Sobibor, and Treblinka were employed to full capacity. The largest genocide in modern history was orchestrated by the Nazi officials at Wannsee and Eichmann appeared to be very content with his “work”.

“I will leap into my grave laughing because the feeling that I have five million human beings on my conscience are for me a source of extraordinary satisfaction,” he stated in 1945. This quote was used as evidence during his trial in Israel in 1961.

Even though Eichmann is often referred to as the leading figure, after Hitler, concerning the “Jewish question” in Nazi Germany, he functioned in a strict chain of command. Specific deportation orders came from Himmler. Eichmann’s office was responsible for collecting information on the Jews in each area, organizing the seizure of their property, and arranging for and scheduling trains.

His department was in constant contact with the Foreign Office, as Jews of conquered nations such as France could not as easily be stripped of their possessions and deported to their deaths. Eichmann held regular meetings in his Berlin offices with his department members working in the field and traveled extensively to visit concentration camps and ghettos.

He was also deeply involved in the extermination of Hungarian Jews, who, by 1944, had experienced far less than Jews in the occupied territories. Hungary broke the alliance with the Axis and was thus invaded by Hitler’s Germany on 19 March 1944. A population of 725,000 Jews lived in Hungary in 1944. That same year 437,000 of them were deported and gassed. The vast majority of the rest was involved in forced labor. During this time, trains transported 3,000 people daily to concentration camps, most of them to Auschwitz.

Eichmann was well known as a fanatical anti-Semite, but even he wasn’t immune to money – or more precisely, diamonds. He was involved in a plot with Rudolf Kasztner, a Hungarian-Jewish lawyer, to help 10,000 Jews avoid extermination and flee to Switzerland. Of course, the personal gain was all that motivated Eichmann, for he received a briefcase full of diamonds after this effort.

Even stranger was the occasion when Eichmann received orders from Berlin to try and negotiate an exchange of 1,000,000 Jewish prisoners for 10,000 supply trucks equipped to handle harsh winter conditions in 1944. This fact proves the desperate situation of the Eastern Front which was, by 1944, completely collapsing. The Allies rejected this proposal, as cooperation with the Nazis was out of the question, but a moral dilemma remains.

After Germany capitulated in 1945, Eichmann used a number of false identities and managed to reach Argentina in 1950, which was the infamous haven for Nazi war criminals fleeing the ruin of their war. Before that he was carefully transported across Europe, living in various different safe houses (some of them being monasteries) and escaping capture.

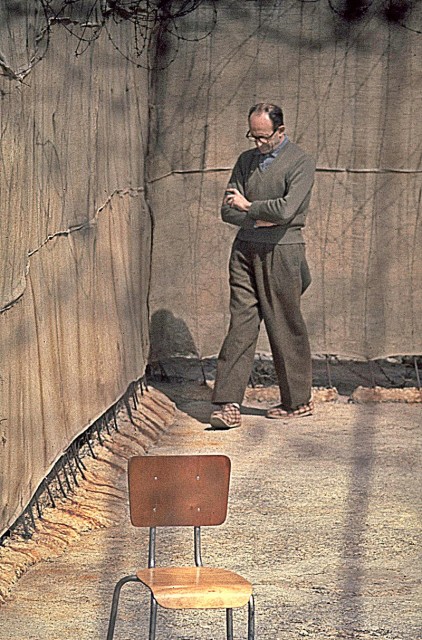

On May 11, 1960, he was captured in a daring operation conducted by Mossad, with the help of the famous Nazi hunter, Simon Wiesenthal who located Eichmann and provided information to the Israeli secret service.

Adolf Eichmann remained convinced of his ideas to the bitter end, even though he tried to deny some of them with ridiculous arguments. His attitude inspired the famous journalist and philosopher, Hannah Arendt, who followed the trial, to coin the phrase banality of evil. Perhaps Eichmann’s speech after he was convicted guilty and sentenced to death explains what Arendt meant by that:

“Long live Germany. Long live Argentina. Long live Austria. These are the three countries with which I have been most connected and which I will not forget. I greet my wife, my family, and my friends. I am ready. We’ll meet again soon, as is the fate of all men. I die believing in God.”

Coming from the mouth of someone who committed such terrible deeds, and yet became completely detached from the sense of responsibility, it is a lesson well learned that warns us of history’s potential to repeat itself.