While many people know the story of the “Little Ships of Dunkirk,” Great Britain was not the only nation to call upon its civilian sailors to come to their nation’s aid. In early 1942 the US Navy and Coast Guard were facing a crisis: they had a massive coastline to protect from U-Boats, and nowhere near enough craft to do it.

Every day they were losing ships to German fire, and weren’t able to produce patrol vessels fast enough to ensure safety at sea. They were searching for a solution, but little did they realize that it was right in front of them.

In 1941, Alfred Stanford, Commodore of the Cruising Club of America, offered his ships and crews to Admiral Ernest J. King, Chief of Naval Operations. But King was an old traditionalist and immediately dismissed the idea of civilians going out looking for submarines. The yachtsmen, though, didn’t relent and created a public outcry. After numerous letters and newspaper articles called for the use of these yachts and their crews, Admiral King finally gave in, and put the volunteers under the command of the Coast Guard, because of their experience with the Coast Guard Auxiliary, a force made up those too old, too young, or unfit to fight.

The Auxiliarists were usually unpaid volunteers, but could be temporarily brought in as paid members of the main fighting force. In 1941 this force stood around 7500 members, with 2-3 thousand craft, most of which were only suitable for inland or coastal operations. The Auxiliary’s main duty at the time was to supplement the Coast Guard’s main force, assisting with safety inspections, lifesaving, as well as patrolling coastal beaches looking for spies and saboteurs.

In May of 1942 the Coastal Picket Force was established, originally under the Coast Guard Auxiliary. The CPF was designed to use auxiliaries and their ships as a screen to keep German submarines from getting access to the coastal shipping of the Eastern U.S. But organizing a such a large force proved too much for untrained civilian volunteers, and the foolhardy adventurers were put under direct control of the Coast Guard.

Finally, the sailors, fishers, and yachtsmen had what they wanted: approval for and a method to create, a fleet of sailing and motor yachts, which could go out and take the fight directly to the U-Boats. It was called the Coastal Picket Force, the CPF, or the “Corsairs.”

The CPF was divided into six groups, from the North Atlantic down to Florida. Manned by volunteer crews made up everyone from college students looking for adventure, to experienced and skilled fisherman the picket ships would each patrol a designated square of 15 nautical miles.

The patrol squares were all located along the 50-fathom line of the Atlantic seaboard, which often meant cruising over 150 miles off the coast. This came as a rude awakening for many of the less experienced sailors, who were expecting relaxing summer cruises, not the often rough seas of the deep Atlantic.

But the ships of the Picket Fleet were sound and seaworthy, often the famous racing yachts of wealthy New Englanders or the fishing schooners of their blue collar counterparts.

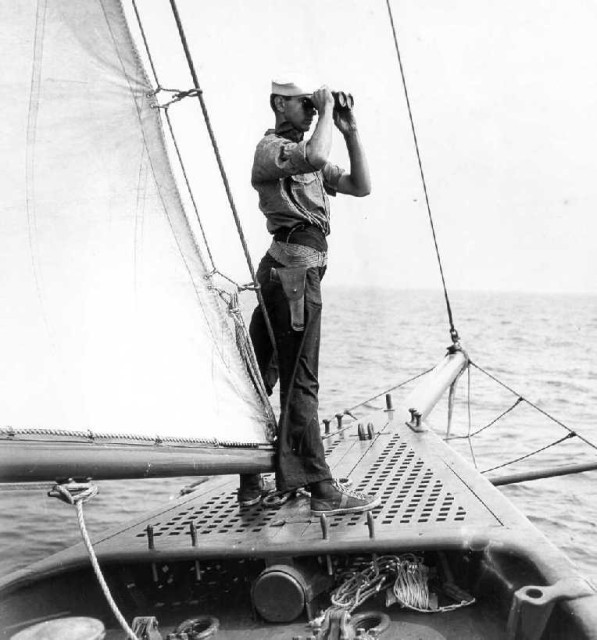

Upon arriving at their bases along the east coast each ship was stripped of its civilian embellishments, including her name, and painted battleship gray with a USCG number designation. But this was about as far as military discipline and uniformity went in this ragtag group of foolhardy men.

Despite their lack of decorum and military style, the ships proved to be effective at their task of sub hunting. The larger, wooden-hulled sailing vessels were especially useful. A submarine’s advantage in wartime is her ability to submerge, but doing so limits their view. To supplement this they used sonar to listen for other ships. But a ship under sail makes little to no noise below the surface, unlike a diesel motor or steam engine.

This made the pickets much harder to detect, allowing them to get closer to the enemy submarines and get a more accurate report on their position. Their lack of noise pollution also allowed them to use sonar much more effectively. Though at times this backfired, one ship, the Valor, called in an airstrike on a submarine, which turned out to just be their refrigerator’s engine misidentified by their sonarman!

Despite this lack of discipline or military skill, though, the ships did prove to be highly effective. John Kimball, a carpenter on the Actaea, shared one account of how effective they could be. While cruising, they located a German submarine just after dawn. The crew was faced with a very difficult decision now: break radio silence and give their position away to the submarine, or keep themselves safe while risking the rest of the American merchant fleet.

The brave crew of the Actaea took the first choice, and radioed in the sub’s position. The entire crew huddled around the radio, not knowing what would happen next. To their surprise, the submarine dove and fled. This proved to be a psychological shift for the German submariners on the east coast: it was no longer open season; they were being watched.

Another instance showed the effectiveness of a line of picket ships, when four of them were all involved in sinking a single submarine. First spotted by CGR-1923 early in the morning, the submarine was next reported by CGR-2516. That evening she was spotted again by CGR 2503. Finally, her position was picked up by a Civil Air Patrol flight, which dropped a smoke bomb. The smoke was seen by CGR-4436 who sped to the location and dropped depth charges. An oil slick was seen, and this became the only possible kill by the picket force.

But this operation also exemplified the combined arms method of sub hunting which had proven so effective. By the time the U-Boat was hit, she had been chased by four picket ships, five Civil Air Patrol Planes, four US Navy Planes, 2 US Navy vessels and a US Navy blimp. While it took a lot to sink a single sub, doing so likely saved scores of lives and hundreds of tons of precious cargo or fuel.

Courtesy of USCG.mil

But the picket ships weren’t just there to hunt submarines.

The picket ships often assisted with rescues, and retrieving lost cargo. CGR-T-2267, the Pioneer, a fishing yawl, was able to rescue all survivors from the tanker R.M. Parker Jr. when she was torpedoed in late 1942. And CGR-355 was able to recover much of the ordnance from the freighter S.S. Benjamin Brewster around the same time.

By the end of 1943 the submarine threat had significantly diminished, and along with it, the need for the Coastal Picket Force. The operation was severely downsized, but not disbanded until the end of the war. It is difficult to say exactly how effective the ships were as they had no confirmed kills – CGR-4436 might not have sunk that submarine – but it did become clear they had won on the psychological front. Because of their presence off the coast, submariners knew that they couldn’t safely cruise the surface at night, and the merchant seamen they were targeting knew that if they sank, there was likely a picket ship nearby which would rescue the survivors.

The story of the Coastal Picket Force has, for the most part, faded into distant memory. But their ability to bring the fight directly to the German U-Boat force not only broke the myth of a submarine’s invulnerability while cruising but also proved to be a useful deterrent for any Nazi ship wanting to torment American shipping lanes.