On the 22nd of January, 1945, 30 Japanese merchant ships sat in Namkwan Harbor, in Southern China. They felt safe in their well-defended home, surrounded by mines, shallows, rocks and tight channels. But that day their feeling of comfort was shattered when torpedoes sped towards them.

An American submarine had found them, the USS Barb, commanded by Eugene B. Fluckey.

Fluckey was born in Washington D.C. in 1913. He attended the United States Naval Academy in 1931 and graduated in 1935 as an Ensign. Before his fateful assignment to the Barb, he jumped around surface ships, and even commanded the submarine USS S-42. But in 1942 he returned to the Naval Academy in Annapolis to obtain a master’s degree in Naval Engineering and then attended the Prospective Commanding Officer’s School in New London, Connecticut.

Upon graduation in 1944 he reported aboard the Barb, as her commanding officer. Few on board would have guessed it, but the most successful combination of man, machine, and crew in American Submarine history had just been created.

From the start, Barb’s new commander proved incredibly competent, and she began to rack up victories. The naval war in the Pacific had swung into the Allies’ favor. Within a few months of taking command, Fluckey earned his first kill, a Japanese cargo ship, the Fukusei Maru, on March 28th, 1944.

Between this first ship, and his last in 1945, Barb, under Fluckey, sank 17 ships, totaling 96,628 tons. Included in this, was the Japanese escort carrier Unyo, a coastal defense frigate, and a converted cruiser. But two very important moments of this command aren’t shown on the list.

The first earned Eugene Fluckey his Medal of Honor. On the night of January 22nd-23rd, 1945 the Barb crawled slowly into Mamkwam (Nankuan Chiang) harbor. He had been tracking a possible Japanese convoy working its way up the Chinese coast. He had finally determined their position but knew he had to play his cards right to make his find count.

When Barb finally spotted her prey, the men must’ve hardly believed their luck. 30 Japanese merchants sat at anchor; a few coastal patrol boats kept watch nearby. They had come in on a completely moonless night, and the enemy didn’t expect anyone to navigate the shallow waters and minefields around the harbor, let alone doing it in darkness. But Fluckey was an amazingly skilled submariner and got his ship perfectly into position.

When he felt confident in his positioning, and the crew knew exactly how they would escape, he let loose a salvo of torpedoes. The deadly steel cylinders sped forward, giving off just a faint trail of bubbles and wake behind them. But when they found marks, they were hard to miss. Explosions rocked the port, as three ships were destroyed. Fluckey surfaced Barb and turned, ready to get out of there. The Japanese patrol boats spotted the lone submarine and gave chase.

While shells were crashing in the water around them, Fluckey pushed his vehicle to the limit. Operating at 150% normal capacity her engines churned, pushing the sub forward at an incredible 23 knots. They dashed out of the harbor, pursued by the patrol ships. Over the next hour, they evaded patrols, the mine fields surrounding the port, and the uncharted and difficult to spot shallows which dotted the area. Amazingly, after this terrifying hour, they made it to open water.

This retreat not only set a world speed record for submarines at the time, but got him, and his crew, out unscathed. For his ingenuity and gallantry in leading his men to this victory, and getting them all out alive, Commander Eugene B. Fluckey was awarded the Medal of Honor. But he wasn’t done yet.

After a quick refit, the Barb set sail on her 12th and final patrol of the war. Fluckey had taken it upon himself to take the war to the Japanese mainland. He equipped the Barb with 5-inch rocket tubes, essentially creating the first ballistic missile submarine.

Creeping up to the Japanese coast, he began a shore bombardment on three towns: with rocket attacks and one more with her regular deck gun. After the final bombardment, Fluckey made his greatest mark on history.

While they were skirting the shoreline to bombard it, Fluckey and his men noticed that troop and supply trains were constantly moving along the coast. They quickly hatched a seemingly insane plan: to land a shore party and destroy one! Onboard, they had 55-pound scuttling charges, the lifeboats would serve to get them ashore, and they would only need eight of their 80 man crew to do it.

But Fluckey didn’t want to unnecessarily risk even one of his crew’s lives. They needed a detonator which would allow the landing party to be far gone during the explosion.

Billy Hatfield, a 3rd class Electrician’s Mate, came up with a solution: a microswitch placed under the rail, when the train passed over it, the rail would sag just slightly, and this would depress the switch, completing the circuit. They had their detonator, charge, boats, and Hatfield made the first member of the crew. Seven other men were selected, Fluckey himself tried to volunteer, but was persuaded to stay on board.

The final shore party was: Paul Sanders, William Hatfield, Francis Sever, Lawrence Newland, Edward Klinglesmith, James Richard, John Markuson, and William Walker.

The night of the 22nd of July, Barb silently crept up to the shoreline, only 950 yards off the land. They dropped their boat; the men climbed in, Hatfield carefully protecting his electronics from the splashing and rolling waters. They rowed in, their team in a mixture of anxiety and excitement.

While landing parties like this had been done throughout the war, and throughout naval history, this was the only time anyone attempted one on mainland Japan during WW2. They hit the land and started working their way forward through the high grass.

Finally, they found the rail line and began digging the small ditch to hold the explosives. Three men were set as sentries, and one sent out to investigate what appeared to be a water tower. As he climbed the ladder, though, he quickly discovered it was an occupied Japanese sentry tower! Luckily, the guard was asleep, and the digging continued, though more cautiously now.

Suddenly a late night express train appeared, roaring down the track towards them. The men all dove for cover, and let the train rattle past. When the night quieted down again, they moved back to their positions. Everything had gone more or less according to plan. The charges were set, no one had been spotted, and now they just had to wire the microswitch.

The men were under orders to evacuate the area, leaving only Hatfield, who built the switch, to install it. This order was completely ignored. The entire landing party huddled over the lone sailor as he fiddled with wires, knowing that one false move could kill every one of them.

At 0132 on the 23rd of July, 1945, the Barb, which now sat only 600 yards off the Japanese coast received a flashlight signal from shore. The landing party had reported mission successful and began paddling back to the ship. 10 Minutes later, an officer yelled to Commander Fluckey that there was another train coming!

Fluckey grabbed his loudspeaker and bellowed to the landing party to “paddle like the devil!”. He knew immediately after the explosion, the whole area would be swarming with Japanese troops, and he couldn’t risk his men being discovered while trapped in a small boat in the surf.

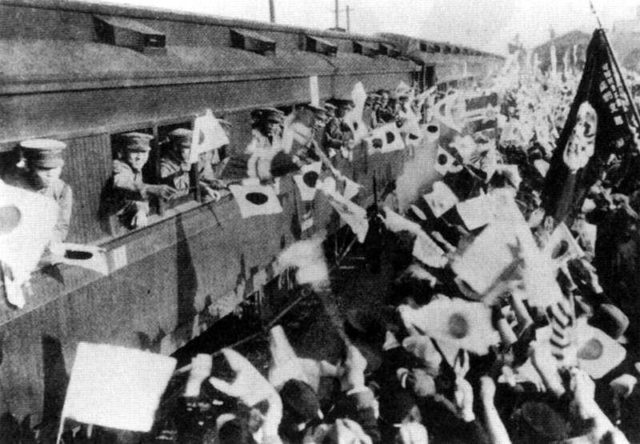

At 0147, the Barb scored the most unique submarine kill of the war. A 16 car troop train sped on to the micro switch. First, the engine blew, sending chunks of burning metal and coal sky high. Then each car accordioned into the one in front, send more flames, sparks, and debris flying about. Fluckey allowed all nonessential crew up on deck to watch; then he quietly guided his ship back home.

In a little over a year, Eugene B. Fluckey took USS Barb on some of the most amazing submarine missions of World War 2. From a near suicidal raid on a well defended and shallow Japanese port, to the first rocket bombardment by a submarine, to finally orchestrating the only invasion of the Japanese mainland during the war.

He earned the Medal of Honor for his bravery, and the respect of his crew for his cunning, daring, and skill. While in he was in command, Barb, suffered no casualties or major injuries.