Nazi Germany invaded and occupied Norway in 1940. Though a relatively poor country (at the time) with only a population of about three million people, Norway had one thing no other country did – the ability to produce heavy water which could be used to build an atomic bomb. The Allies tried to destroy the facility several times, but it took Norwegian commandos to finally bring it down.

The Vemork Hydroelectric Power Plant in Rjukan, Norway opened for business in 1911. Located near the Rjukan waterfall, it was the world’s biggest and was devoted to the processing of nitrogen for use as fertilizer. Then in 1933, the Norwegian Institute of Technology suggested a method of isolating heavy water from normal water through electrolysis for use in scientific study. The process required a lot of energy, and the Vemork plant was ideal.

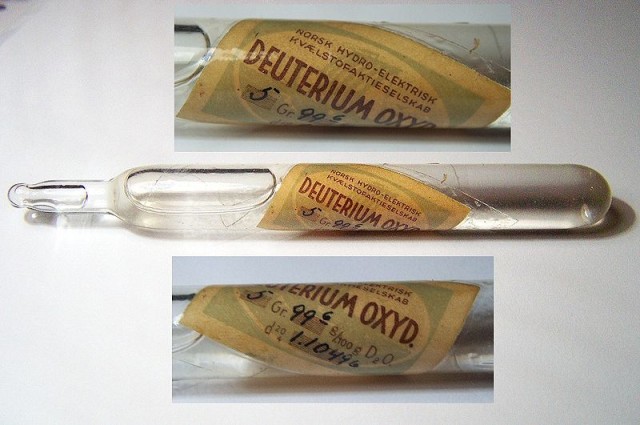

The following year, the scientific community began proposing nuclear fission as an alternative form of energy. Then in 1939, German scientists published an article about how nuclear fission might be done using various materials such as uranium and deuterium. Naturally, it didn’t take them long to consider the military applications of atomic power.

Considering Germany’s rapid militarization, France panicked and bought all of Vemork’s stock of deuterium in 1940. Then in April of that year, Germany invaded Norway, so French agents snuck it out and brought it back to France. Unfortunately, France was also invaded in May, so the substance was sent to Britain to keep it out of German hands.

But the Vemork was now under Nazi control and was still able to produce heavy water. Given how advanced German technology was, few had any doubts that they would eventually develop an atom bomb. So now the race was on to develop one before the Germans did. To buy themselves time, the British had to take out the Vemork.

The Special Operations Executive (SOE – a British organization devoted to espionage, reconnaissance, and sabotage operations in Nazi-occupied territories) launched Operation Grouse on 19 October 1942. Many Norwegians had fled to Britain when their country fell to help the Allied cause against Germany, some of these were trained to be commandos.

Operation Grouse involved sending four Norwegian commandos who knew the terrain to Rjukan to act as an advanced force. This group was called the Swallows, but they had landed far off-course, requiring a long march through sub-zero temperatures while avoiding detection. Because they had been separated from some of their supplies, they resorted to eating moss to stay alive.

Then Operation Freshman was launched on 19 November 1942. British engineers were flown into the area and were to meet up with the Swallows, but they failed. Most of the operatives died on the way – some because they crashed on a mountainside, others at the hands of the Gestapo. Realizing that Vemork was an important target to the British, the Germans beefed up its security.

So the SOE launched Operation Gunnerside on 16 February 1943. Six more Norwegian commandos, trained in explosives, were to join the Swallows. They were parachuted in by the Royal Air Force and met up with the half-starved Swallows after several days. By the time they reached Vemork, the facility was surrounded by mines, floodlights, and extra German soldiers.

Among Vemork’s staff was another Norwegian agent (also trained by the SOE) who provided detailed sketches of the interior, as well as shift schedules. Since the failure of Operation Freshman, the Germans had become slack, focusing on the area surrounding the facility, but not the interior of the complex.

There were only three ways to reach the plant: (1) via a single-track rail which entered the building, (2) a guarded bridge over a ravine, and (3) the ravine with icy water at the bottom. The operatives chose the ravine because the water was at its lowest point in winter.

Making it to the other side, they slipped out of their camouflage suits and into British Army uniforms so that they would not be confused with local resistance fighters. If the Germans thought the latter were responsible, they’d would kill or imprison some of the locals.

The men entered the building through a cable tunnel into the main basement when they were caught by the caretaker. Fortunately, he was a patriotic Norwegian who hated the German occupation and offered to help. The men planted their explosives around the heavy water electrolysis chambers and timed them all for a delayed detonation… but then they had a problem.

The caretaker had misplaced his glasses. With the war on, supplies were low and he couldn’t easily get a replacement. So the men had to waste precious minutes scouring the basement looking for his spectacles. They finally found them and exited the building, making sure to leave behind a Thompson submachine gun which was only available to the British military.

The explosions destroyed all the heavy water produced since the German invasion, more than 1,102 pounds of it. Also ruined were the equipment required to produce more.

The saboteurs split up – five crossed over into neutral Sweden, some 248 miles away. The rest stayed in Norway, resulting in a massive manhunt involving 3,000 soldiers and thousands of gallons of precious fuel. But their quarry refused to leave – they wanted to help more anti-German actions from their native land.

Operation Gunnerside was so successful that Vemork was only fully operational again by April. Since the Americans had finally joined the war, a joint Allied bombing of Vemork was launched in early November. Despite dropping 711 bombs in broad daylight, it did no good. The Allies had timed the raid at noon since that was when the workers were on their lunch break. Nevertheless, about 600 bombs missed their target, causing a number of civilian deaths.

Ten Norwegian commandos had succeeded in doing more damage than an entire aerial squadron armed with hundreds of bombs. The SOE deemed Operation Gunnerside to be its most successful sabotage mission in WWII. And since commandos were a new force, Gunnerside’s success ensured that they would remain important in the British military. Many other nations later copied the commandos and developed their own special forces units.