William “Wild Bill” Donovan is widely known as the “father of American Intelligence.” His determination to create a centralized counterintelligence unit paved the way for the modern CIA. Despite pushback from various government agencies and personnel, he persevered, showing everyone the meaning behind his infamous moniker.

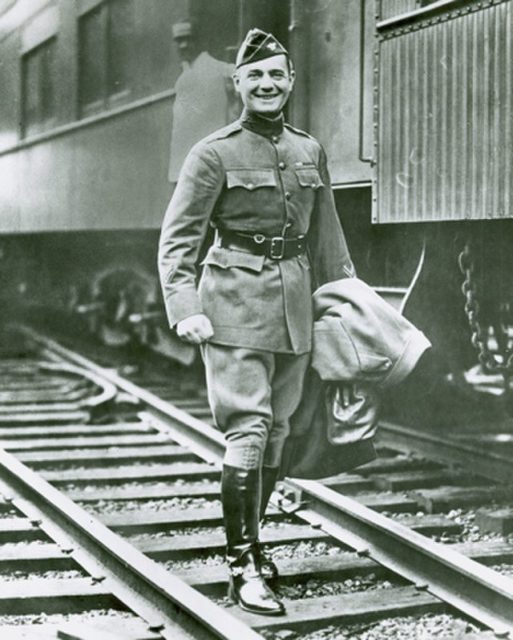

Bill Donovan was a decorated war hero

Bill Donovan fought with the 165th Regiment during the First World War. He’s said to have been a demanding leader who often pushed his troops to the limit. His team was an integral part of the Second Battle of the Marne in July 1918, and their presence was noted during the Meuse-Argonne Offensive in October 1918.

It’s rumored that Bill got his nickname during the war. Legend has it that he made his battalion run a three-mile obstacle course, after which the men fell to the ground, out of breath. The 35-year-old chastised them, saying, “What the hell’s the matter with you guys?” to which a soldier responded, “But hell, we are not as wild as you are, Bill.” From that day on, he was known as Wild Bill, a moniker he publicly denounced, but secretly loved.

When the war came to an end in November 1918, Bill had been injured a total of three times. He’d risen to the rank of full colonel and had become one of the conflict’s most honored and decorated soldiers. Not only did he receive two Purple Hearts, but he was also awarded the Silver Star, the Medal of Honor and the Distinguished Service Medal, among others.

A need for central intelligence

When World War II broke out in 1939, intelligence operations in the United States were split between nearly a dozen government agencies. They didn’t get along and viewed each other as rivals, especially when it came to getting a portion of the government’s annual budget. This didn’t go unnoticed by other nations, with Britain in particular pointing out it would impact America’s effort during the war.

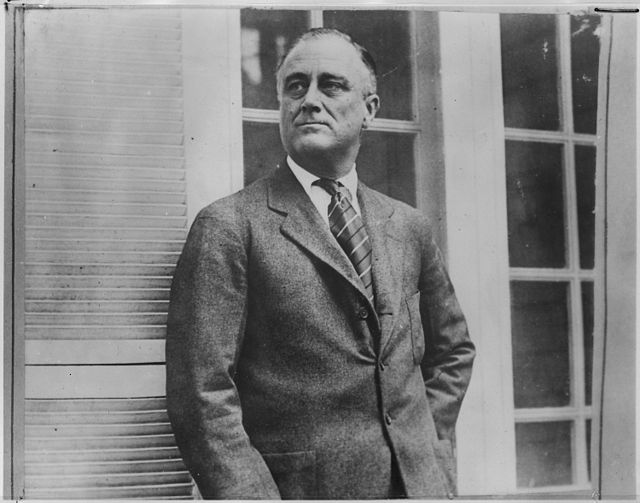

In the summer of 1940, Bill Donovan, by then a successful lawyer, was invited by Canadian airman William Stephenson to be the president’s envoy to Britain. Franklin D. Roosevelt hoped the trip would allow the war hero to see if the United Kingdom had the capabilities to withstand an attack by the Germans. British Prime Minister Winston Churchill also saw an advantage in the trip, as he hoped Donovan could convince Roosevelt to provide more aid in exchange for intelligence information.

Donovan was briefed on Britain’s new Special Operations Executive (SOE) unit, designed to infiltrate occupied Europe and help resistance groups. It provided them with supplies and directed them in attacks against German communication and supply lines, hindering their primary method for spreading propaganda.

Upon his return to the US, Donovan met with Roosevelt to share his belief that the country needed something similar. While the president was cautious about the idea, the other intelligence agencies were against it, with FBI director J. Edgar Hoover calling the idea “Roosevelt’s folly.”

Creation of the Coordinator of Information

On June 18, 1941, Franklin D. Roosevelt used his executive powers to create the Office of the Coordinator of Information (COI), with Bill Donovan at the helm. His plan was for the agency to gather and analyze information that would then be used to engage in secret operations.

Headquartered in a nondescript building overlooking the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, DC, it was a largely civilian operation. With control over the hiring process, Donovan enlisted associates, people with travel experience and individuals with knowledge of global affairs. He was also not a typical leader, urging his employees to be creative and think outside of the box, wanting them to find innovative solutions to difficult problems.

Once he had his staff, the first order of business was to evaluate incoming information that in-house propagandists could use to demoralize the German Army. He also set up espionage schools; oversaw the invention of new guns, bombs and cameras; hired female spies; and made connections globally – all to engage in his unorthodox version of warfare.

On the outside, the COI was simply gathering information and releasing propaganda. However, the public was not informed of these espionage activities, as the US hadn’t officially entered the war. That changed after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.

The COI becomes the Office of Strategic Services (OSS)

A few months before the attack on Pearl Harbor, on July 11, 1941, Franklin Roosevelt changed the COI to the Office of Strategic Services (OSS). While Bill Donovan was allowed access to more government funding to “wage secret war around the globe,” it meant it was no longer a White House agency.

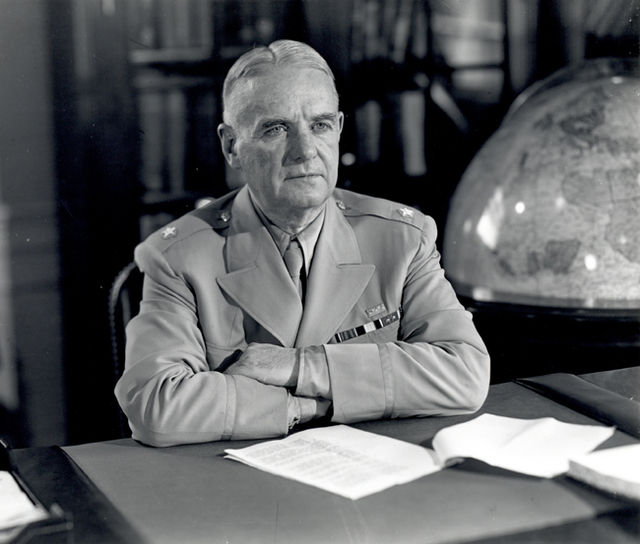

Placed under the rule of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, the OSS began allowing military personnel into its ranks. While still considered a civilian agency, its staff was three-quarters military. It was during this time that Donovan donned his uniform and rejoined the US Army, as it officially joined the war.

The espionage work done by the OSS allowed for many successes during the war. It allowed for the successful Allied Invasion of North Africa in 1942, and it was credited with the 1944 Allied landing on the French Riviera.

However, despite this success, the OSS did have its detractors. While initially the inspiration behind its inception, the UK was suspicious of the agency and incredibly distrustful of any OSS operations occurring on British soil. The Philippines also blocked the OSS access, on account of Gen. Douglas McArthur‘s antipathy.

The CIA emerges during the Cold War

Bill Donovan was interested in keeping some version of the OSS around after the end of the Second World War. In November 1944, he sent a memo to Franklin Roosevelt, requesting the establishment of a permanent worldwide intelligence agency.

The OSS would be dismantled after the war, but another central counterintelligence agency replaced it: the CIA. It emerged a few years into the Cold War and was similar to its predecessor in many ways – it was even operated by old OSS members.

However, there was one key difference, in that then-President Harry Truman refused to allow Donovan to head the agency. Instead, he gave the position to Adm. Roscoe Hillenkoetter.

Donovan continued to aid in the CIA’s formation behind the scenes and offered them intelligence whenever he could. This was to the disapproval of Truman, who considered him a “meddler.” He was eventually offered the position of American Ambassador to Thailand, which he accepted, before returning to his law career.

More from us: 9 Facts About The CIA They’d Probably Like To Stay Secret

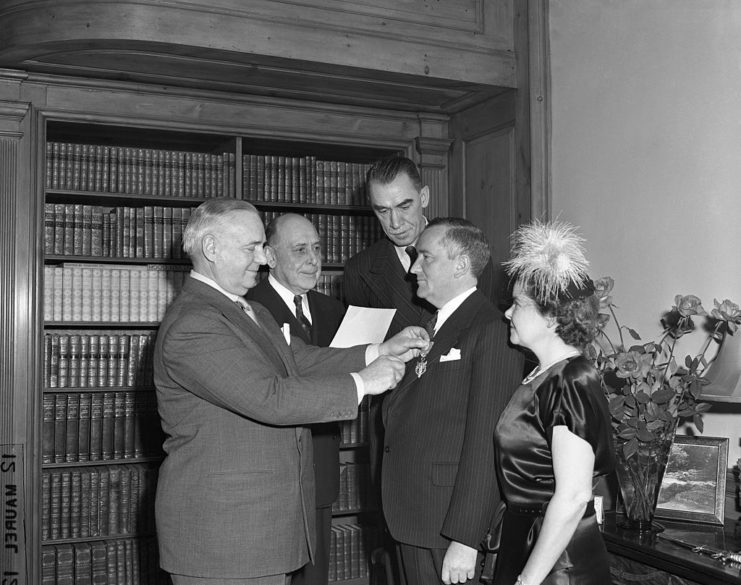

While stationed in Thailand, Donovan started showing signs of dementia, which ultimately took his life on February 8, 1959. In his memory, a statue was placed within the lobby of the CIA’s headquarters in Langley, Virginia, honoring his role in the agency’s history.