In the relatively short history of the United States, the country has gone through turbulent, violent and just plain crazy times. One of the weirdest and most memorable was Prohibition, a 13-year period that nearly everyone looks back on and asks, “Why?”

For over a decade, the sale, production and transportation of alcohol were outlawed, but humans did what humans do and found ways to circumvent the restrictions while enjoying alcoholic beverages away from the watchful eye of the police. One person who did this was Winston Churchill, who didn’t feel like going “dry” during a trip across the pond.

Why did the United States enter into the Prohibition era?

The idea of banning alcohol had good intentions behind it, with officials looking to reduce domestic violence and crime while also improving public morals. It followed a century-long effort in the United States to free the country from “the tyranny of drink,” as many viewed it, with the Temperance Movement at the forefront. According to supporters, society needed to exercise moderation and avoid alcohol, as it was associated with Satan.

Congress passed the 18th Amendment, which put restrictions on all things alcohol, in December 1917. Just over two years later, at midnight on January 17, 1920, Prohibition officially began, meaning it was illegal to manufacture, transport and ingest alcohol.

Alcohol was obtained in illicit ways

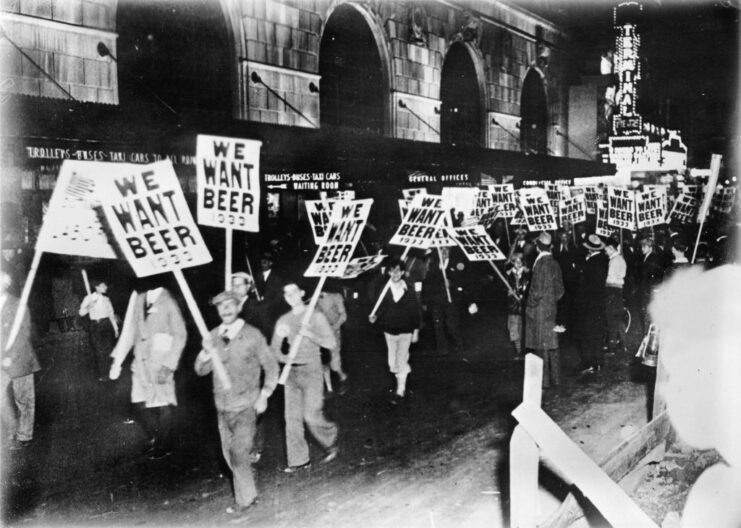

Prohibition came with unintended consequences that turned the era into one of the most lawless in American history. Criminals took over control of the production and distribution of alcohol, and many otherwise lawful citizens partook in the illegal activity of purchasing alcohol in secret establishments known as “speakeasies.”

Many in the United States found their own ways of getting alcohol, including people in power. This led to the era of speakeasies, moonshine and bootleggers, the latter of whom went to great lengths to get alcohol to those who wanted it (and therefore money in their pockets).

Gangsters like Al Capone also took advantage, leading to the revolution of America’s criminal underworld. Prohibition as a whole was an opportunity to grow their illicit enterprises, and many groups turned from public menaces to “organized” outfits that used public demand for alcohol to develop successful, secretive businesses.

Circumventing Prohibition

One of the ways some American citizens accessed alcohol was through, of all people, their own doctors. During Prohibition, the Treasury Department allowed the drink to be prescribed for “medicinal” uses, which many took advantage of.

The arrangement was a mutually beneficial one, as doctors were paid well for this service, while “patients” received a pint. They could pay around $3.00 every 10 days for the prescription and another $3.00 or $4.00 for the alcohol itself.

This was amplified by professionals in the medical industry, who praised alcohol as a miracle drug able to help fight cancer and cure depression. In just the first six months of Prohibition, 15,000 doctors applied for permits that enabled them to “prescribe” alcohol to patients.

Winston Churchill was injured while visiting New York City

Prohibition affected everyone in the United States, even visitors, and Winston Churchill was no exception. He visited the country in 1931 to speak about the “Pathway of the English-Speaking Peoples.” Famous for his enjoyment of cigars and alcohol, this likely was not a fun prospect for him.

While in New York City, the future British prime minster attempted to cross a street near Central Park, but looked right, instead of left, due to the differences in moving traffic directions between the US and the United Kingdom. Thinking the route was clear, he stepped onto the road and was subsequently struck by a vehicle traveling at 30 MPH.

Fortunately, Churchill wasn’t killed in the accident, suffering just a cut on his forehead, a sprained shoulder and bruising on his chest.

How did Winston Churchill bypass Prohibition in the United States?

If you thought Winston Churchill was the kind of man to enjoy a few glasses of alcohol while making his recovery, you’d be right. However, as he was in Prohibition-era America, the British Bulldog’s only legal option was, of course, his doctor.

Otto C. Pickhardt prescribed the 57-year-old “the use of alcoholic spirits especially at mealtimes.” How much was he allowed to consume? An amount that is “naturally indefinite,” with a minimum of 250 cc daily.

More from us: Famous Heroines Who Refused to Take a Step Back During World War II

Churchill survived his close call with death and was nursed back to health with a helpful, unlimited supply of “medicinal” alcohol. While laying in his hospital bed, he couldn’t have imagined that, in just under a decade, he’d be leading the Western stand against fascism.