When the Japanese invaded New Guinea in early 1942, they began a struggle for control of the island which would last until the end of the Second World War.

Advancing on Australia

The Japanese effort at the start of World War Two was focused on conquest. Expanding across the Pacific and the east Asian mainland, forces sought to conquer territory for the Japanese Empire, and, in particular, to drive out western influences in the region. By 1941, they had expanded far south and Australia was in their sights. As well as providing armed forces, Australia was an important source of supplies for the Allied war effort in the Pacific.

The largest land mass on Japan’s route to Australia, New Guinea had long been divided between the western colonial powers. Since the end of the First World War, it had been divided into three territories, one governed by the Netherlands, one by Britain and one by Australia.

In January 1942, Japanese forces invaded New Guinea.

Invasion

Initial landing on neighbouring New Britain and then at Salamaua on the north side of the New Guinea mainland, the Japanese began a push south towards Port Moresby. The mountainous centre of New Guinea proved an obstacle to the Japanese and an asset to the defenders, who held them up with successful guerrilla attacks.

Another Japanese force, heading for Port Moresby by sea, was stopped in its tracks at the Battle of the Coral Sea. Meanwhile, the Allies sent in more troops of their own, including the Australian 6th and 7th Divisions, which had returned from Europe to fight the Japanese. By June, they had over 400,000 troops on New Guinea, the vast majority of them Australians. The Allied forces were led by General Douglas MacArthur.

Jungle Fighting

Fierce fighting now took place in the New Guinea jungle, as the two sides both tried to take control of two areas – Buna and Milne Bay. An Australian advance up the narrow track to Buna was halted on 23 July when Japanese forces, recently brought in by sea, faced them at Wairope. The Australians held for four days before being forced back, as overwhelming numbers of Japanese reinforcements arrived.

The Australians continued their courageous rearguard action in the face of a persistent Japanese advance. Retreating troops inflicted heavy casualties on the Japanese while air attacks also whittled away at them. Suffering from over-extended supply lines and the sweltering jungle heat, the Japanese struggled but pressed on.

The advance ended on17 September when the Japanese reached Ioribaiwa. They had been ordered to stop their while resources were focused on fighting at Guadalcanal. This temporary halt would mark the final limit of their advance.

The Allies Attack

On 28 September the Allied counter-attack began, led by General Blamey.

The preceding months had turned the Australians into experienced jungle warriors while neither the Americans nor the Japanese were adjusting as well to conditions in New Guinea. Australians pushed the Japanese steadily back over the next few months, taking Kokoda, Gona, Buna and the Japanese base at Sanananda.

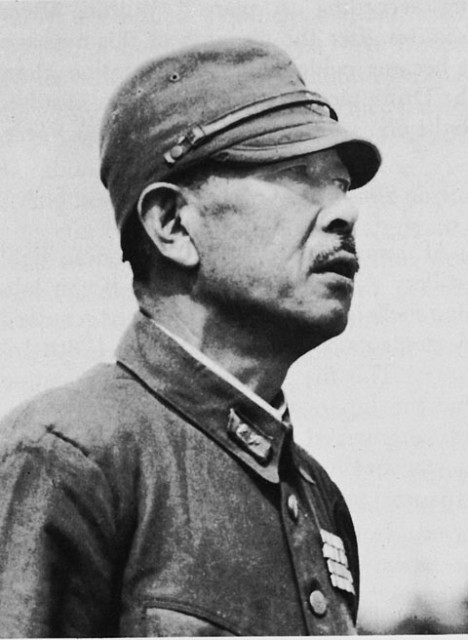

The Japanese were taking terrible casualties – 12,000 men lost, compared with 2,800 Allied soldiers. General Horii, the commander of the Japanese forces, drowned while trying to cross the river at Wairope, and was replaced by General Adachi.

Wau and Withdrawal

After Sanananda fell on 22 January 1943, Japanese forces fled west. Reaching the airfield at Wau, they launched an attack on 30 January but were repulsed by local troops, taking a further 1,200 casualties. An attempt by the Japanese to reinforce these troops ended in disaster when a convoy was sunk on 3 March during the Battle of the Bismarck Sea, drowning 3,000 soldiers.

Digging in around Mubo, Adachi was determined to hold Salamaua beyond it, which he considered vital, using 9,000 of his 11,000 soldiers to protect it. But an Australian advance took Mubo and forced the Japanese to abandon Salamaua, which the Americans took on 11 September.

Again, the Japanese lost many more men in this fighting than their opponents, with nearly five times as many dead.

A Two-Pronged Attack

Splitting their forces, the Allies began a two-pronged advance. The Australian 7th Division advanced down the Markham Valley to cut off the Huon Peninsula while the Australian 9th Army and American troops used amphibious landings to hop along the Huon coast.

By November 1943, the Allies had made great advances, and General Macarthur called a pause. While the Allies rested and provisioned, the isolated Japanese suffered.

Clearing the Enclaves

In January 1944, the advance began again. A landing by the US 32nd Infantry, accompanied by an Australian advance from recently captured Sattelberg, cut off 12,000 Japanese troops on the Huon Peninsula. General Adachi and his remaining 30,000 men retreated towards Wewak, where the Allies left them with 20,000 civilians and limited supplies.

Adachi tried to break out of this trap but was stopped by the US II corps. This time, the Japanese lost nearly 20 times as many dead as the Allies, and there was no breakout.

Rather than try to attack Adachi head on, MacArthur chose to leave pockets of Japanese scattered without supplies around New Guinea. Amphibious landings let the Allies break their opponents up, preventing them making any decisive action.

It was left to the Australians to make the last great advance of the New Guinea campaign, taking Wewak on 11 May 1944 after a terrible trek through the jungle.

The Patient General Adachi

Adachi had no chance of fulfilling his aims or taking an active part in the rest of the war. But he did not give, and New Guinea remained a war zone. He held out for another year, only surrendering at the very end of the war, along with 13,500 of his men.

The fighting in New Guinea was marked by patience and persistence on both sides, which drew the fighting out, and by terrifyingly disproportionate losses on the Japanese side.