Since our childhood, stories of fighter pilots being awesome have always been the subject of our fantasies. But even the most valiant fighter pilots of today seem like amateurs to the pioneers who set standards of such achievements that could teach Chuck Norris a few tricks. We’re talking about the fighter pilots of the Second World War.

Almost until the end of World War II, the United States Army Air Corps (USAAC) believed in the idea that “a bomber will always get through”. Hence, any and all advancements that were made in aviation were included in the bomber planes. Fighter planes were generally simple and unsuitable for such combat, since the bomber pilots were believed to be able to fend off enemy fighter pilots on their own. Putting it simply, fighter pilots were assigned planes that were held together by metal and good intentions.

So, imagine the daring it took to create heroes who took what they had and made the most of it, without complaining.

Bill Overstreet is regarded as one of the American veteran aviators who, in the words of Robert Frost, took the path “less traveled by” and created a trail for aspiring fighting pilots to tread on.

Born in Virginia on April 10, 1921 as William Bruce Overstreet Jr., Bill was working as a statistical engineer when the Japanese attacked the Pearl Harbor. He quickly enlisted and became a private by the February of 1942. He completed his preflight training in Santa Anna, California and after several months, was sent to Rankin Aeronautical Academy.

One thing you need to know about the Rankin Aeronautical Academy: It was basically your favorite action movie protagonist’s training dojo. Except with planes flying at hundreds of feet above ground. Trainers used unusual methods to test the new recruits’ limits, one of the favorite techniques being leaving the landing of a 500-feet above, upside down Stearman to a surprised trainee, with the engine cut.

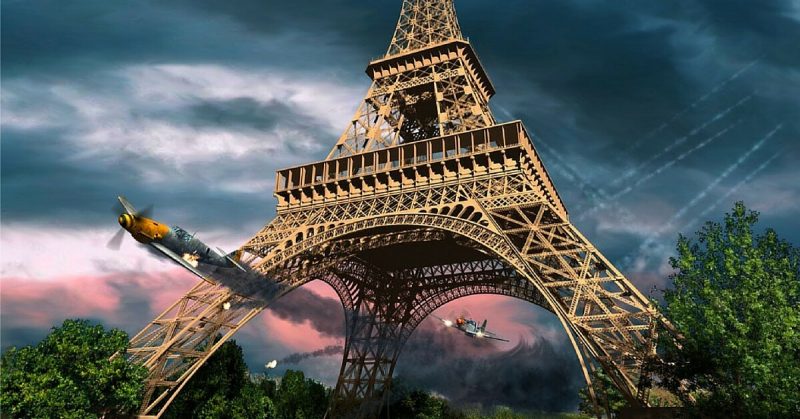

As action movies will tell you, being trained by people wild enough to go to great lengths to teach you how to survive tends to rub the crazy on you and turns you into someone destined for greatness. You can attest this fact as true since Bill Overstreet accomplished something that the United States and France still talk about: he chased a German Messerschmitt Bf 109G underneath the Eiffel Tower’s arch in his P-51C Mustang in 1944.

While Overstreet, now in the 357th Fighter Group, was in solo hot pursuit of the German pilot, the enemy had reckoned that the anti-aircraft artillery on the ground would do away with the American, but they had seriously underestimated Overstreet, who maneuvered through the intense enemy flak and shot the German plane.

Compromised and seeing no other way out, the German pilot made an unbelievable maneuver flying under the arches of the Eiffel Tower. But little did he know that he had met his match as Bill Overstreet remained hot on his trail and followed him through the arch, scoring more hits and all the while shooting off the Nazis on the ground. When asked about it, he said:

“It was no big deal. There’s actually more space under that tower than you think. Of course, I didn’t know that until I did it.”

When asked by an interviewer what he remembered from that day about Paris, he commented:

“I’m not sure. I was a little busy.”

Taking down an enemy pilot alone with the anti-aircraft artillery all around, following an aircraft through the arches of Eiffel Tower, and escaping the artillery by flying low on the water; yes, of course he was busy.

The best part is that this was not Bill Overstreet’s only achievement. The man had trouble following him throughout his life, like a child following candy, all of which he turned into adventures.

He met one of his freak accidents in June 1943 while flying a Bell P-39 Airacobra in his combat training. It was backed up by many pilots’ deaths that if an Airacobra entered into a flat spin, it was fatal. Bill Overstreet, being the badass that he was, went on to become the first pilot to survive an Airacobra’s plummeting crash.

While practicing aerobic maneuvers with his mates, Overstreet’s plane went into a devastating flat spin. He first tried to control the plane and when he saw that he couldn’t, he tried to release the doors, but the air pressure prevented the doors from opening.

Had we been there with uncontrollable controls and jammed doors, we certainly would’ve screamed ourselves to our impending death. But Bill Overstreet was no ordinary man. Undeterred, he overcame the air pressure by pressing one knee and one shoulder to the doors with all the strength that his adrenaline-charged body could offer.

The door crashed open and Overstreet pulled the ripcord of his parachute on the spot. He was so close to the ground at that instant that, even his squadron mates didn’t see his parachute deploy. The moment he had deployed his parachute, he found himself standing right among the ruins of the Airacobra just beside the propeller.

Bill Overstreet’s “one second jump” earned the young trainee quite the fame. His feat with the P-39 was later declared “combat ready”, a title alluring to what any pilot would be if they managed to survive an event with a former 100% fatality rate.

“Southern Belle” was the name Bill decided for his first P-51 Mustang. After it was lost, he named all of his assigned P-51s as “Berlin Express”. Once, his oxygen was cut off by anti-aircraft flak and he flew for ninety minutes purely on reflex in his subconscious state. Somehow, he recovered and flew the plane safely back home.

Not bad for someone who fainted while flying over a Nazi-occupied territory.

He later one-upped this achievement by flying blind.

Flying with a sinus infection and during a chase, he engaged in a power dive which resulted in swelling of his eyes due to the change in pressure and they clamped shut. He kept the plane airborne just by feel, and landed with radio help.

Bill Overstreet’s tour of duty ended in October of 1944 and after being released from active duty, he served as an accountant till the age of 65.

He was awarded the Legion of Honor in 2009 at the age of 88. He died on December 29, 2013.

Main image by Len Krenzler / Action Art