In 1942, the Battle of Midway sealed the fate of the war in the Pacific. The course of the remaining campaigns was fairly certain. However, the cost of achieving the goal of defeating Japan was not. The enemy was still determined, fanatic, with no will to surrender. Although Japan could no longer act as before, it was still a formidable foe on land, sea and in the air.

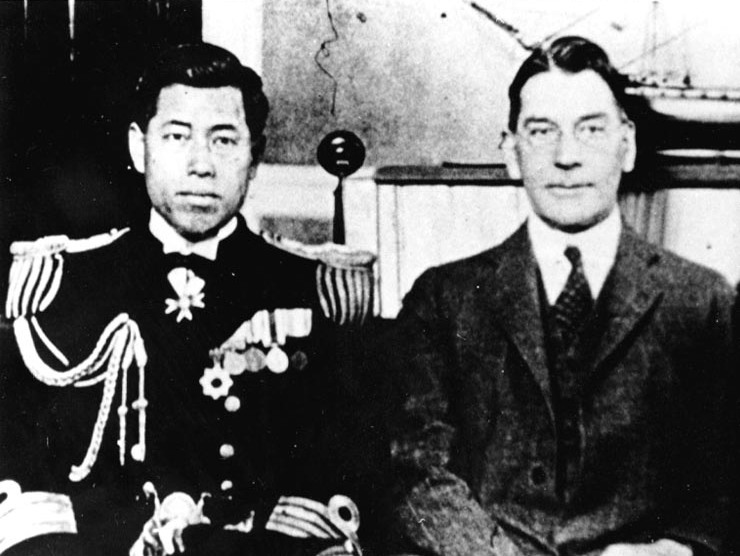

One notable leader for the Empire of the Sun was Isoroku Yamamoto. The famous architect of the attack on Pearl Harbor was indisputably the most recognized admiral of the Japanese Imperial Navy. Yamamoto was well-educated, talented, highly intelligent, and respected by both sides of the conflict. He spent several years in America and studied at Harvard. He became familiar with a western customs, traditions, and most importantly, the potential of the United States.

Isoroku Yamamoto was against the war with the United States, or even joining the Tripartite Pact. He had no illusions about winning the war but served his country as an honorable man. Knowing that Japan chose a wrong route, he supported his country as best as he could.

“In the first six to twelve months of a war with the United States and Great Britain I will run wild and win victory upon victory. But then, if the war continues after that, I have no expectation of success.” – I. Yamamoto

“Get Yamamoto”

On April 14, 1943, American cryptologists intercepted and deciphered a peculiar note about a planned inspection by Yamamoto in the Solomon Islands. The message contained many details, like departure times, locations, exact route, even the number and types of aircraft assigned to this mission.

Altogether, it became the raw material of an assassination attempt on his life. Franklin D. Roosevelt didn’t have any second thoughts when he was introduced to the plan. The mission had been approved by every man in the top three days later and marked as top secret and urgent. Important as it was, planning and execution were two different things.

“In preparing for battle I have always found that plans are useless, but planning is indispensable. “

Dwight D. Eisenhower

Operation Vengeance

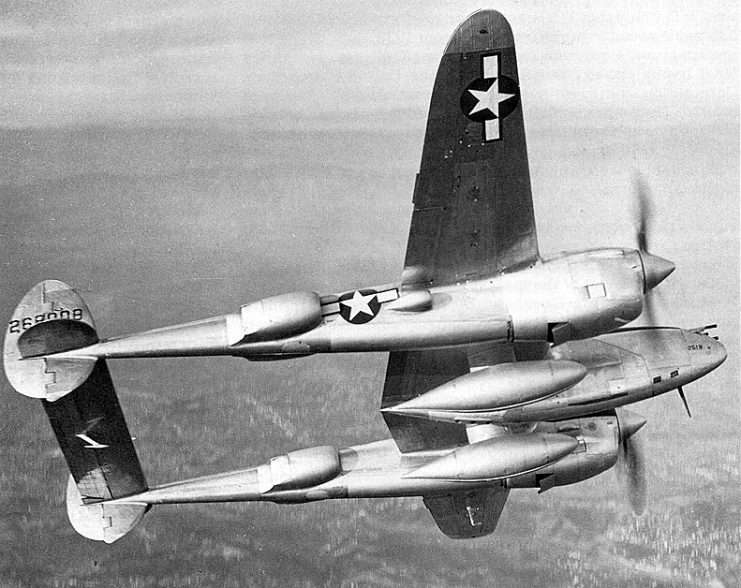

The P-38 Lightning was chosen to conduct this mission since the distance, including turnabout course was far beyond any other aircraft in the American arsenal. A single USAAF squadron of eighteen P-38s was assigned to the mission, and all they knew was to “intercept a high ranking officer.” One out of four was designated to be a “killer” while the rest had to cover the striking force.

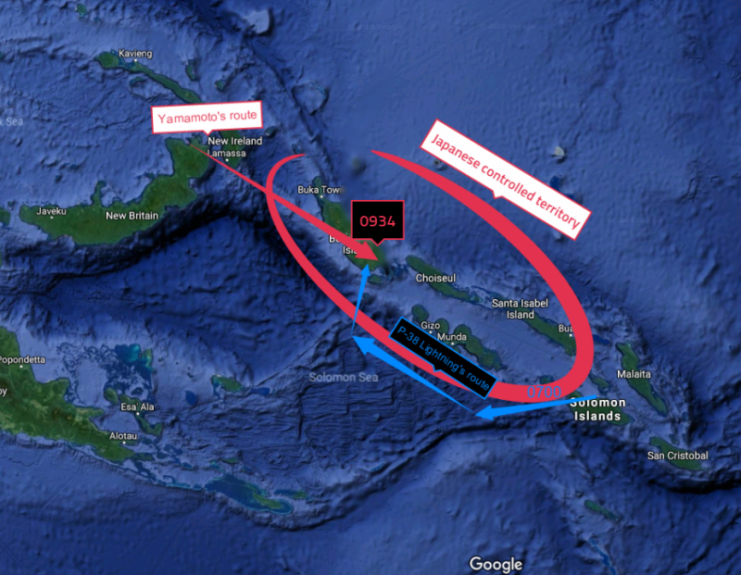

Yamamoto’s route, assuming he would travel in a straight line from Rabaul to Balalae Airfield, took approximately 315 mi (507 km). Based on that, American planners had to predict the time and place of the clash, hoping for no delays nor course changes of the Japanese pilots.

General Mitchell, the author of the plan, calculated the “interception” at 09:35, a couple of minutes before Isoroku’s landing on Balalae. Precise navigation was also a problem so the “Fork-Tailed Devils” were equipped with navy compasses.

On the morning of April 18 at 07:00, only sixteen Lightnings took off from Kukum Field because two had malfunctions. Additionally, the squadron had to avoid enemy radar and coasts by flying low at 40 ft above sea level in complete radio silence and cross 400 miles (640 km). Even then, there was only a slim chance of success.

However, everything went according to the initial plan and no changes were made by either side. The dogfight started at 09:34 near Bouganville. The American pilots spotted two enemy Mitsubishi G4M bombers along with an escort of six Mitsubishi A6M Zero fighters.

First Lieutenant Rex T. Barber opened fire on the first Betty, hitting the right engine which caused heavily smoking and the aircraft crashed into the jungle. This was the plane with Admiral Yamamoto on board. The second bomber carrying Vice Admiral Matome Ugaki was shot down by Lt. Besby F. Holmes afterward and it crash-landed into the sea. Ugaki survived the attack and was rescued later. Barber and Holmes each claimed one Zero shot down, but Japanese records show no fighters destroyed. Nevertheless, one P-38 piloted by Lt. Raymond K. Hine was lost.

Aftermath

Admiral Yamamoto’s body was found next day. He had been hit with two 0,50 cal bullets and he died before the crash. His body was cremated and shipped to Tokyo aboard the IJN Musashi, his last flagship. Future commanders-in-chief of the Combined Fleet, Mineichi Koga and Soemu Toyoda, were not able to control the combined fleet as effectively as Yamamoto.

Ironically, a trip to boost Japanese morale ended with a devastating blow for Japan. The Japanese public was officially told about the loss of their admiral a month later. On the contrary, the operation raised morale in America as one of their most dangerous enemies had been eliminated.